Jardins Des NationsRestaging Global Governance in GenevaArchitecture of Territory

“Together, let us assume that the Earth is one small garden.”

Gilles Clément, The Planetary Garden and Other Writings, 1992.

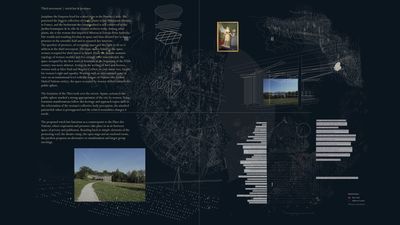

The crucial infrastructures underpinning the contemporary urban realm are mostly invisible, and it takes a crisis or a breakdown of some sort to bring them into view, observed anthropologist Susan Leigh in her work. She further observed that the role of research and design is to expose and scrutinise these invisible systems in order to ensure their just and equitable use. These observations resonate well with the recent experience of the Covid-19 pandemic, when institutions of global governance, in particular the World Health Organisation, burst into media spaces around the world. In contrast to their powerful role in the media, the urban presence of the WHO and other international institutions located in the city of Geneva remains relatively marginal. To borrow from Leigh, these institutions remain “invisible” in the city and detached from everyday life.

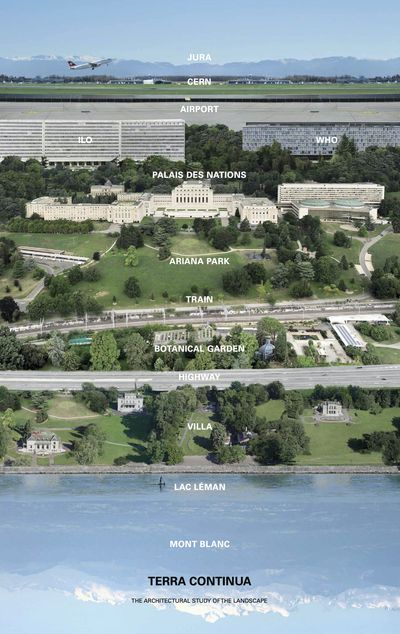

The image of the “city of peace” and the seat of world governance in Geneva is still highly appealing. Located in the cuvette surrounding Lac Léman between the Jura and the Alps, Geneva has maintained an appearance of a small and well-organised city, a home to efficient apparatus of international institutions and organisations. But in times of crisis of capitalist urbanisation, the ecological crisis, and the rise of nationalist tendencies across Europe and the world, coalescing in the recent events of the pandemic, the institutions including the United Nations, the World Health Organisation, and the International Labour Organisation, all located in Geneva, are struggling to assert their leadership and to retain influence.

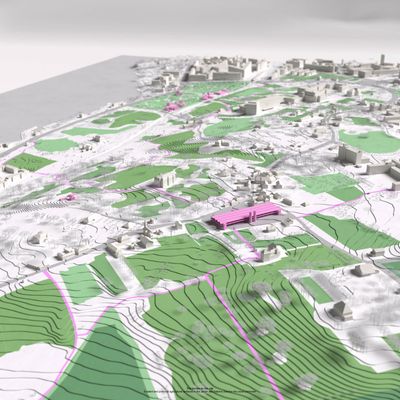

The described challenges provoke questions about the character of urban spaces and landscapes of International Geneva. Due to the high level of security sought by international institutions and organisations, much of the area is inaccessible to the public, with many parks and gardens serving as mere backdrop, or a buffer, shielding the complex and untransparent inner workings of organisations. On select public walkways, groups of tourists are usually being guided between the monuments—however, since the start of the pandemic, any public visits have been halted, further underscoring the detached character of the area.

The wider urban ramifications of the growing cluster of Geneva’s international organisations include soaring rents in the inner city, which have pushed many working residents to look for housing in the French periphery. With thousands of employees and hundreds of associated services and activates, International Geneva is one of the key economic protagonist in the city and the region, but its urban role for the city is weakly articulated. As things stand, it appears that the international institutions are hosted by the city of Geneva, but remain largely independent from it.

The notion of the Jardin des Nations links back to the birth of internationalism and institutions of international governance, a process which unfolded throughout the nineteenth century and culminated in Geneva with the competitions for the League of Nations around 1927. A few institutions, including the Red Cross and the International Labour Organisation, had by that time already arrived in this area on the northwest fringes of Geneva, which had become known for large summer estates of Genevian elite, for vineyards and gardens, and for leisure promenade along the lake with Jardin Botanique.

Only in 2005, for the first time, the municipality of Geneva tried to address and reframe the urban character of the international quarter with a concept plan (Plan directeur) entitled Jardin des Nations. The intention of the municipality has been to open many of the closed estates and institutions to the public, linking them into a new framework of public spaces and landscapes accessible to the citizen. However, until today, almost none of these ideas have been realised.

Jardin des Nations diploma invites the student to engage with the urban space of International Geneva, in order to rethink the constitution of urban political spaces, and the urban and architectural representation of institutions of global governance in the 21st century. How does global political cooperation and common decision-making work in times of decentralised societies, media and information technologies? How do globalised political spaces, such as the space of the Covid-19 politics, intersect with the physical space of the city? Should international political institutions engage with the city and its everyday life? How and where can democracy be exercised in public? What kind of values do we want institutions of global governance to represent? How can those values be projected and represented in public space and landscape? Can this site with high security demands become open, public and diverse? Finally, can the metaphor of the Garden—as in Jardin Planétaire by Gilles Clément—inspire a vision of a space and society, based on the principles and values of diversity, inclusivity, and Nature? Can the Garden metaphor inspire a new design approach to Geneva’s international quarter?

The diploma students were invited to contribute ideas and urban design proposals for international Geneva. Taken together, all students projects have a cumulative value, describing a potential common vision for the area, a complementary project to the municipal Plan directeur Jardin des Nation.