Nobody Is an IslandLeslie R. Majer

The low-lying coastal areas of Denmark, Germany and the Netherlands are under increasing water pressure: storms are increasing in intensity from the seaward side, while sea levels are gradually rising. Sea levels are expected to rise by up to 100 cm by the year 2100. On the mainland, storm surges are displacing more and more freshwater from the adjacent catchment areas and estuaries. The governments of the federal states near the coast are therefore planning to massively upgrade the continuous dyke line along the coast. In 2021, after the flood in the Ahr valley, the German federal government will also issue a flood protection guide for private property protection and structural precautions. On a large and small scale: it’s all about protection. Walls and fronts are built where natural movements of the landscape and people confront our understanding of static safety.

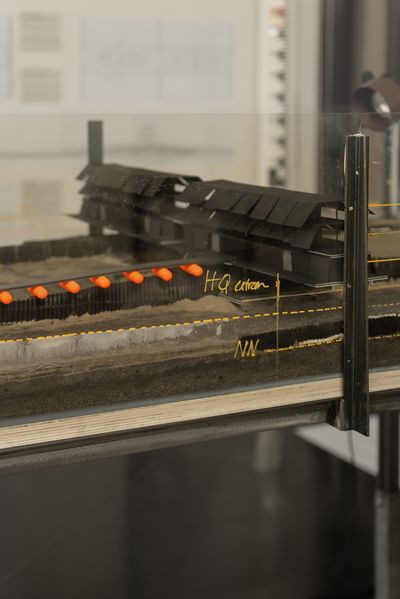

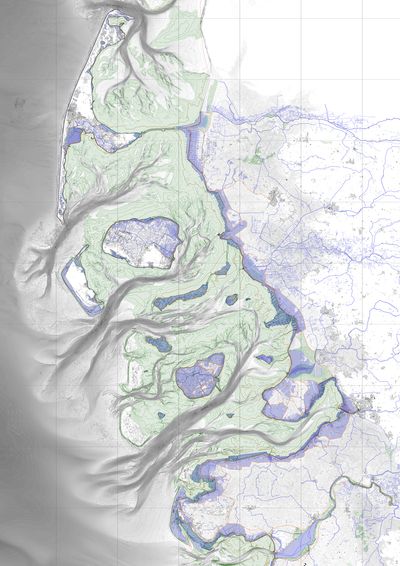

The free master’s thesis Nobody is an Island deals with the role of architecture in a changing landscape using the example of the North German coastal areas of the Wadden Sea. As an embedding scenario, it is proposed to break up the linear paradigm of coastal protection via elongated walls of earth (dikes) and to reflood low-lying areas behind the dikes. The water, which is carried several kilometers a day by the tides, could thus carry sediments inland: over a certain degree of entropy, the soil would grow up again and the immensely diverse ecosystem of the Wadden Sea would slowly migrate inland with the sea level. In this rewetted zone, coastal infrastructure is needed to break the wind and waves and accumulate sediment at the same time. At a distance of 250 meters from the opening of the dyke, the State Office for Coastal Protection is placing lahns and groynes in the form of full tree trunks, in keeping with the centuries-old tradition of coastal protection, which break the incoming waves and stabilize the ground. The strict separation into nature conservation area and building zone is dispensed with and a new relationship between these two entities is proposed: It is assumed that house and ground are inextricably linked and only make each other possible in a new understanding of vernacular building.

Oscillation Map.

- New tidal zones until 2100

- Dykes

- Tideland

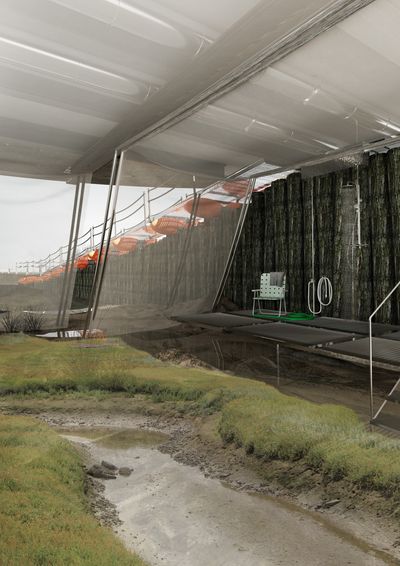

The experience and inhabitation of the moving elements and the simultaneous collective protection goal of the coast is expressed in a collective architecture: these existing pile foundations as a coastal protection element are used as the basis for a new building. Without distinguishing between stilts and house, the architecture itself is an accumulation structure: a light wooden building is created, which is founded on soft marsh and mudflat soil and whose first floor is flooded daily for six months every six months. In summer, the first floor becomes an extension of the living space used by tourists. In winter, when the intensity of tourism and agricultural use decreases, it is flushed with seawater twice a day. In a region like this, which lives from agriculture and summer tourism, 90 % of new buildings are vacation apartments. As a health resort, its population increases 10-fold in the summer months. The landscape; sea air, Wadden Sea, views, bathing experience—the unique movement of the tides, the natural conditions of the landscape—is the region’s capital. The architecture is surprisingly unaffected by this movement, apart from the temporary minimal architecture of the beach chairs on the dykes and beaches. In winter, these generically idyllic apartments are empty. More than simply adapting to the more extreme climatic conditions, the architecture in this project becomes a mobile actor; a dwelling that transforms from house to pier in the different seasons and loses a storey. The house works with rather than against the external roar and collects mud that is transported in the stormy water.

This work was co-supervised by Tom Emerson and Milica Topalović (2nd supervisor).