BatamBatam Industrial IslandLivio De Maria and Stephanie Schenk

The island of Batam in Riau Archipelago was designated as Indonesia’s first industrial zone in 1971 in order to benefit from the proximity to Singapore. At the beginning of the 1990, Batam remained scarcely inhabited and covered with rainforest. Two years later, several companies had begun manufacturing activities on the Indonesian island and thirty-five more had already agreed to set up activities in an industrial park. At the same time, a second island, Bintan, was added to the scheme and designed to operate as a planed resort. Since then, Singaporean investments have been decisive for the rapid industrialization and urbanization of the two major islands in Riau Archipelago.

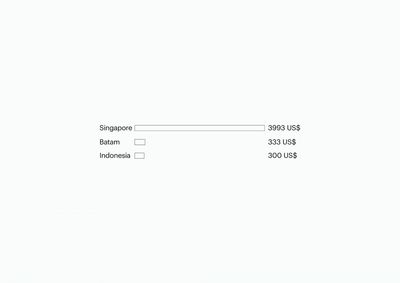

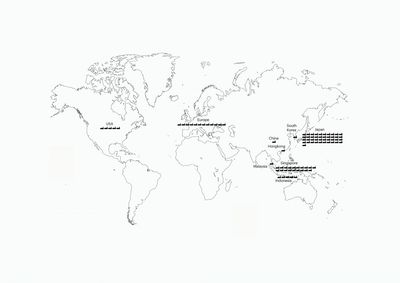

The emerging metropolitan region Singapore–Johor–Riau is fast growing, both in terms of population and economy, with a population of around 8 million today. The region is dominated by a strong centre and is profoundly asymmetric: the large landmass of Johor extends to the North, while Riau Archipelago is dispersed to the South; Johor is economically wealthier, it has a longer history and tighter connections to Singapore than Riau. It is estimated that 300,000 residents of Johor Bahru are based in Singapore for work while 150,000 more commute daily to work in the city-state. On the other hand, seasonal workers and maids from Riau work in both Singapore and Johor. Riau Archipelago is still dominated by industrial manufacturing (Batam) and tourism (Bintan), while Johor Bahru seems to be transforming into a service economy extending from Singapore. Culturally, the region is unified and part of the Malay world, with the exception of the Chinese dominated city-state.

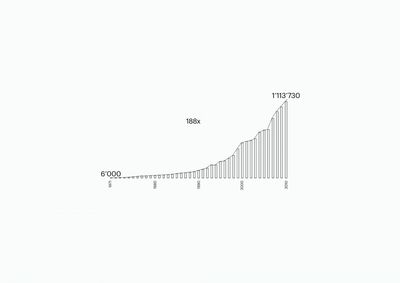

After its independence in 1965, Singapore rapidly transformed from a relatively undeveloped colonial outpost into one of the most developed nations in Asia. Within three decades, the city-state joined the First World economy, despite its small population, limited land area and lack of natural resources. From early on, it focused on offering cheap labour and welcoming foreign direct investments and multinationals. This allowed Singapore to rapidly establish itself, as one of the four Asian Tigers with one of the highest GDP growth rates in the world through the 1970s. Gradually, policymakers sought to switch from the low profit manufacturing of low cost products, toward a production with increased wages, requiring higher skill and higher productivity.

During the 1980s, it became clear that the continuing growth of Singapore’s economy required more space and workers beyond the limits of the city-state. At the same time, changing political circumstances allowed for an onset of regional economic cooperation. Through the so-called Growth Triangle agreement among the three countries, Singapore offered to provide management expertise, technology, telecommunications and transportation in exchange for land and labour offered by Johor and Riau. As a result, vast tracts of land have been opened up for development, mainly industrial production, dominated by Singaporean investment. Particularly since the early 1990s, the phenomenon of migration of the manufacturing sector from Singapore and the formation of the productive hinterlands in Johor Bahru and Riau became apparent.

Since 2006, the legal format of the cross border cooperation has been refined through the establishment of special economic zones (SEZs) and the free trade zones (FTZs) that have been set up on the Malaysian and Indonesian sides in order to further capitalise on the relationship with Singapore. Owing to various incentives, involving tax reduction, abolition of customs duties, possibility of ownership, and certainly the access to land and labour, “the special zones” now represent a warm pool for both Singaporean firms and the multinationals.

The study attempts to analyse and describe the productive territory of Batam and Riau Archipelago, the Indonesian side of the metropolitan hinterland.