Illia's CoastSeaside CountrysideAndres Ruiz Andrade and Johannes Hirsbrunner

“Seaside Countryside” is a distinctive typology of coastal development of Peloponnese. Since antiquity, the coast of Peloponnese has been an area of commercial activity, but was also perceived as dangerous and unfit for inhabitation due to piracy, conflict and swampy land. Most historical cities had been located inland, at a distance from the coast.

In the mid 20th century, Peloponnese had still resisted beach tourism: the growing urban middle class in Greece still preferred to escape the city to the mountains for vacation and leisure. Only in the 1960s and 70s, coastal tourism begins to flourish, mainly through public incentives, such as Xenia project, in form of large-scale tourist facilities designed and built at various locations throughout the country.

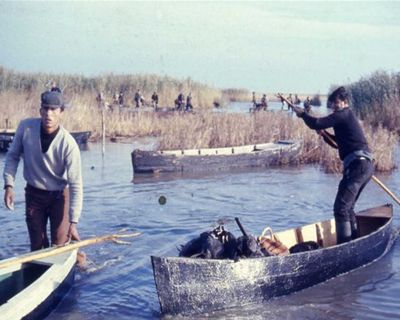

The coast of Ilia is part of low-lying plains on the west of Peloponnese, forming a foreland to the north-south mountain ranges. Pyrgos, Ilia’s largest city, is located about four kilometres inland. The coastal topography was transformed profoundly over time; in antiquity the coastline laid approximately eight kilometres further inland. The present-day coast formed through the build-up of alluvial soil, made cultivable in the second half of the 20th century through extended irrigation infrastructures.

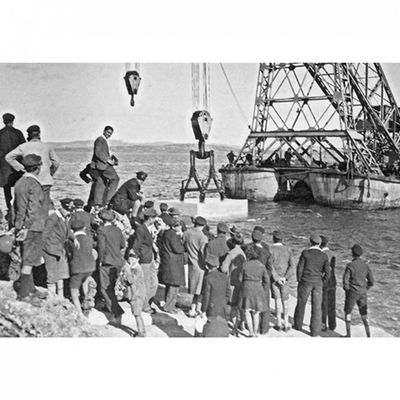

Sited on a rocky cape, Katakolon is a unique point on the coast and has been a port settlement for centuries. From the end of the 19th to the mid 20th century, it functioned as the gate for export of Ilia’s agricultural products, especially raisin, to Europe. In recent years, the Port Katakolon has experienced major makeover through cruise tourism—an ongoing development with uncertain consequences. The port now receives around 300 cruise boats annually, serving as the gateway to the archaeological area of Olympia, located twenty kilometres inland.

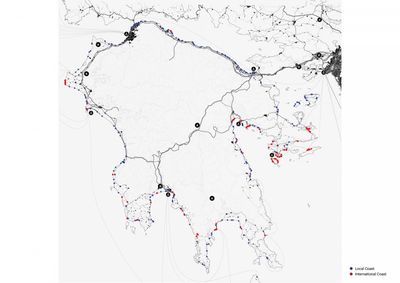

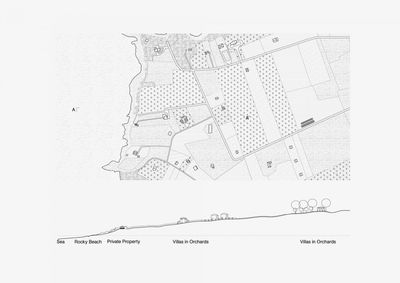

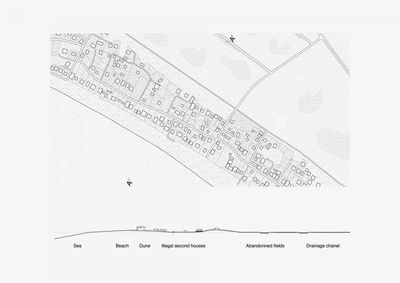

Urbanisation of Ilia’s coastline is heterogeneous and largely spontaneous: Illegal beach settlements, campsites, summer houses with olive orchards, and new seaside resorts catering to international tourist are lined up side-by-side. The extended coastal zone between the cities (Pyrgos, Amaliada) and the sea functions as a peri-urban landscape, filled by vegetable fields and farmhouses, water reservoirs and irrigation channels, and scattered leisure sites such as motorbike trails and hiking paths.

Ilia’s coast appears to develop without strategic land-use plans. The planning and building regulation in Greece generally focuses on the construction aspect of development; the floor area ratio and the minimum plot size are widespread regulatory instruments. By contrast, zoning plans cover less than 3 percent of the Greek countryside territory, an important exception compared to most European countries, contributing to unauthorised construction. The proportion of unauthorised construction in Greece increased 45 percent between 1950 and 1995. Initially, the mechanism of self-built housing served as a response to the pressing housing shortage, but since the 1970s the practice spread beyond housing to include holiday houses and other tourist establishments. The lasses-faire attitude and the policy of non-demolition since the 1950s can be interpreted as powerful elements of local and national politics and electoral games in Greece, which radically altered the urban landscape of the country.

In contrast to congested touristic coast of the northern Mediterranean, the coast of Ilia is an interesting exception. Not a purely touristic destination, rather, it is appropriated by the locals. The seaside is here still an area of agriculture and second residence connected to nearby inland cities. On the other hand, various pressures including increasing transport infrastructures and tourist arrivals are threatening the local character of the coast and the preserved ecosystems.

Through maps, drawings and text, the project describes the specific local character of Ilia’s coast, seen as an attractive mixture of local seasonal living, agriculture and protected nature areas. The “seaside countryside” is offered as a concept and potential for the future of the area—a proposal to envision an alternative territorial hierarchy, resisting the wholesale submission to international tourism, and strengthening the features of the local urban landscape.