Countryside and Construction—Fshat i NdërtimitArchitecture of Knowledge: Education in Craft and ConstructionGjokë Daka, Caspar Trueb, Lorin Wiedemeier, and Denis Muça

Throughout the landscape of Southern Albania, there is evidence of ancient Ottoman structures and ruins, vernacular stone houses in the mountains and brutal communist monoliths inspired by Russian, Italian and German occupation. However, since the fall of communism in 1992, the building tradition finds itself in a time of rapid transformation. Knowledge and building techniques are slowly being lost to modern construction processes and the rich built fabric is slowly becoming dominated by cheap, unfinished concrete frames. Only in village or city centres, one can still find historical structures.

The surrounding buildings date from the 18th and 19th century. The urban morphology has not changed much since then. Photograph: Wikipedia

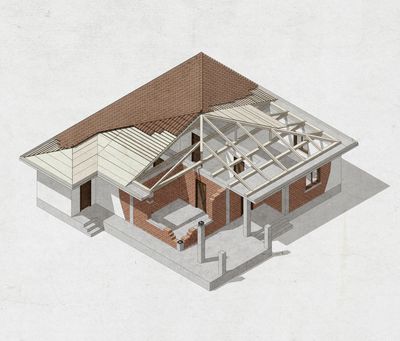

This building technique encourages the construction of rather large structures which are then partially left unfinished due to a lack of capital. these "incomplete" buildings are intended to accommodate the growing family in the future, once the money is available. Source: Mikel Tanini.

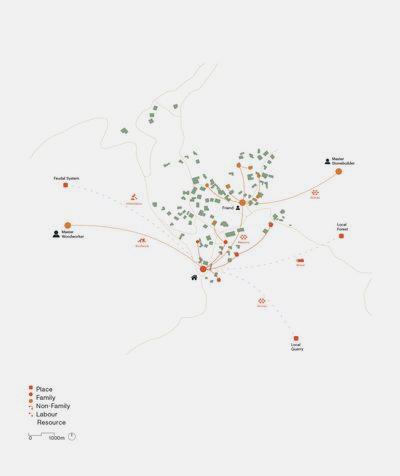

Socio-economic relations, cultural heritage and local customs are embedded within the construction, materials and labour networks, in particular of residential buildings. We distilled four prevalent housing typologies in four different locations: a traditional vernacular construction in Dhoksat, an Ottoman architecture in Gjirokastër, a reconstruction of a house with traditional techniques in Leusë, and an informal housing in Sarandë.

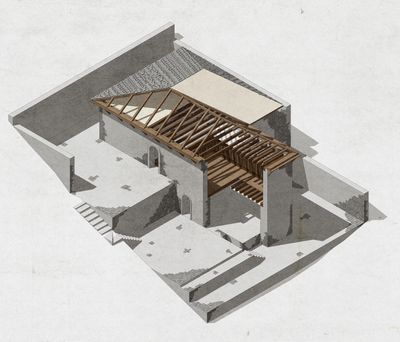

Traditional vernacular construction in Dhoksat

Dhoksat is one of the most authentic villages in the region of Lunxhëri, with cobblestone roads and traditional stone houses. It is well known as “the village of master stone masons.”

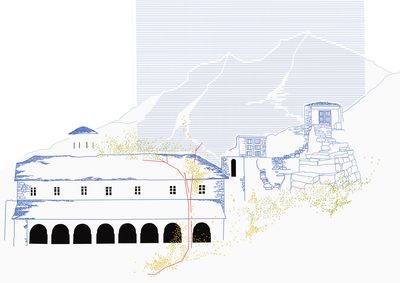

Ottoman architecture in Gjirokastër

In Gjirokastër, the richness of housing typologies is the result of many years of activity of the Albanian upper middle class in the administration of the Ottoman Empire.

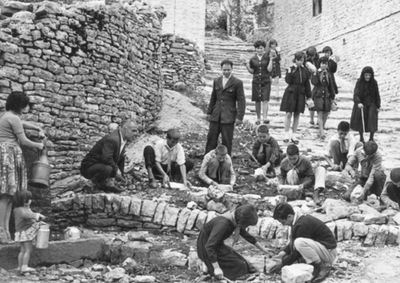

Reconstruction of a house with traditional techniques in Leusë

Leüse is known as “the village carved in stone”—all roads and houses are composed from regional stone. During the Second World War, the village was almost completely burned down by the Nazi forces. Reconstruction began during the communist regime and people were instructed to rebuild the village with the local stone and traditional techniques.

Informal housing in Sarandë

The migration from rural areas into urban areas, the lack of affordable housing, the absence of clear ownership rights and planning regulations facilitate the formation of informal urban sprawl in cities such as Sarandë. As a consequence, these spaces often lack connection to the public transport network and social infrastructure.

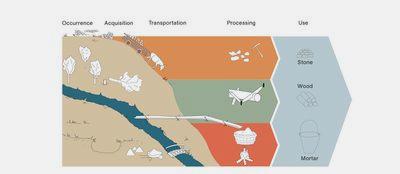

Construction Techniques and Networks

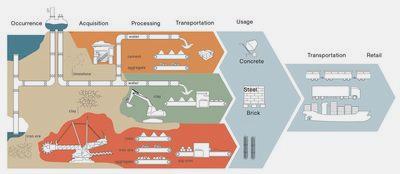

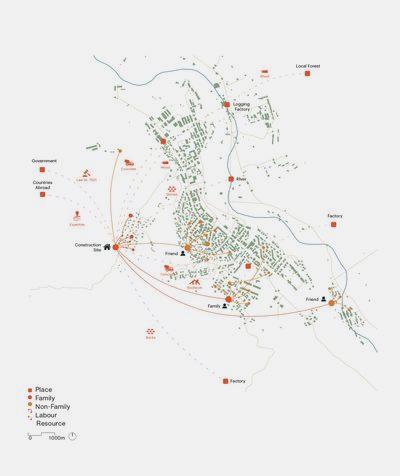

The materials usually come from near the site, but the labour force and expertise are brought in from specific locations, since the knowledge about these construction methods are not widespread.

Labour and expertise come from nearby, but materials and resources often come from industrial production sites which are rather not located in small villages.

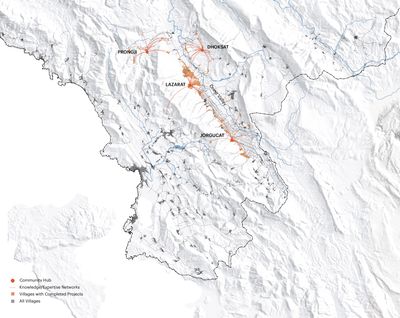

Creating a Network of Building Construction Workshops in the Drino Valley

We see a huge potential in developing building construction systems that are small-scale, ecological and rooted in traditional construction methods. In order to preserve the latter it will be key to disseminate the knowledge. New institutions such as training centres and workshops could include sustainable construction in their curriculum and support the mutual exchange of workers and expertise.

Two workshops would be held every year, consisting of three stages—first organisation, then planning and site evaluation, and finally construction and expertise. Every five years, a concurrent project would be to setup a new hub in a different city, expanding and solidifying the network. The new hub will of course be a testament to the therein taught curriculum. Over time, the workshops and training centres will diversify and specialise in specific knowledge to reach a wieder audience. Thereby, a network of training centres and workshops for traditional and ecological construction methods will unfold in the Drino Valley and change the built landscape.