AtlasAgronica: Agrarian UrbanismYufei Li and Jonas Zimmermann

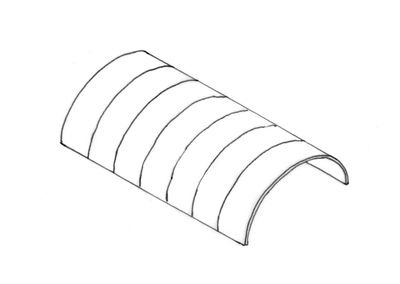

It is a beautiful day and you are resting in the shade under an arched roof panel. The only sounds you hear are the shuffling of hooves and the soft mooing of cows grazing in the open field, a distant laugh coming from the podium, and the low hum of farm machinery. The flexible walls, hanging roofs, as well as movable platforms rearrange themselves as they traverse the flat grass land.

Source: Tijn van de Wijdeven.

The Second World War had many impacts on society and architecture did not remain unaffected: In Italy, designers and architects sought new directions as a direct reaction to the modernist movement and its entanglements with the the fascist regime. Andrea Branzi—co-founder of the Archizoom Associati, an Italian avant-garde group—criticised the modern movement for only focusing on geometries and clearly defined functions, ignoring agriculture and its productive systems. In an imaginative, science fiction-like approach, commissioned by Philips Electronics through Domus Academy, he proposed new ways of looking at architecture and urbanism conceiving a new urban form: Agronica.

“We sought to overcome the concept of opposition betwen two territorial realms, agriculture and architecture, which were nothing other than two different ‘morphologies’ of the same logic.”—Andrea Branzi

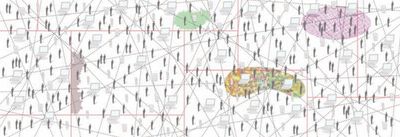

At the end of the 20th century, digitalisation and other new technologies were changing the way we live and work. In response, Branzi argued that architectural form should no longer be determined by function. Instead, architecture should encourage more flexible living and working, where office activities could be carried out even in a farmhouse or a disused power plant. Accordingly, the historical concepts of “The City” and “The Countryside” would no longer exist. Instead, settlements become part of metabolic and symbiotic systems in which functions separate and disperse, only to group together in new combinations; the meeting of food production and consumption, residential spaces and agricultural and activities. This new metropolis is what Branzi calls a “weak system that guarantees the survival of the agricultural and natural landscape.”

Source: Branzi, Andrea 2012.

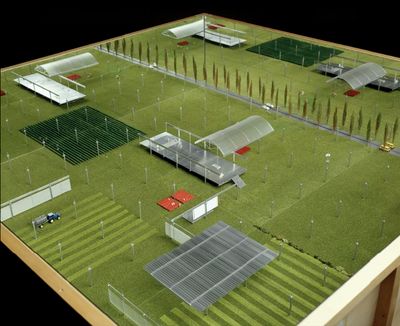

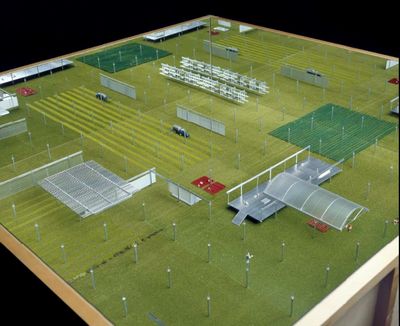

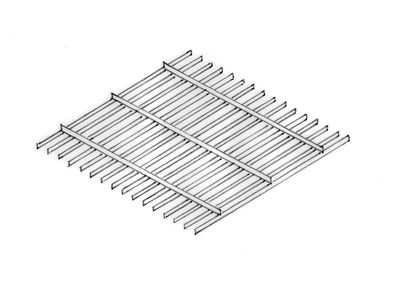

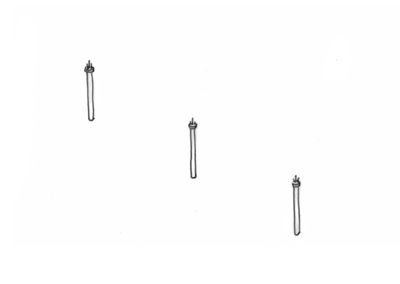

Agronica aspires to synthesise landscape and city, agriculture and architecture. It is a flat landscape with a regular grid of pillars on green fields. On this seemingly infinite plane, fields are cultivated and cows graze freely between objects. Agriculture is conceived as a system of environmental transformation which is able to adapt to reversible programming and is powered by weak, seasonal and eco-compatible energies. It is capable of self-regulating the inhabited space and its rules of operation using advanced support technologies.

“As an incomplete utopia, it is not based on the advent of new technologies but on the desire to go beyond the boredom generated by the old question of uniqueness of the identity of places and the unity of the project.”—Andrea Branzi

YouTube

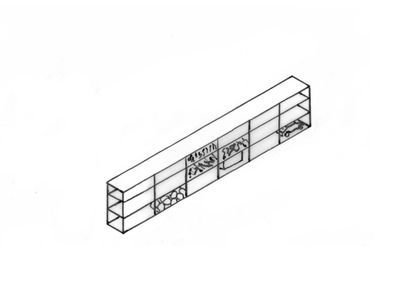

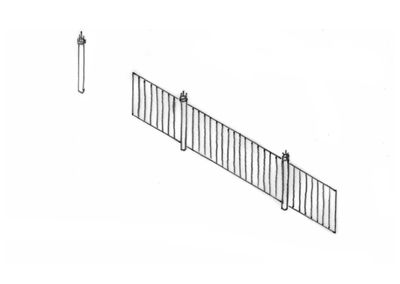

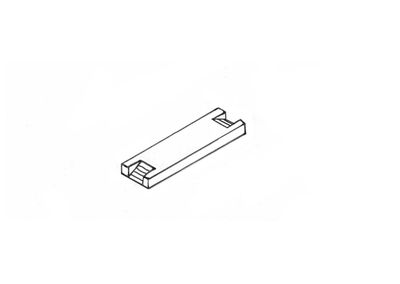

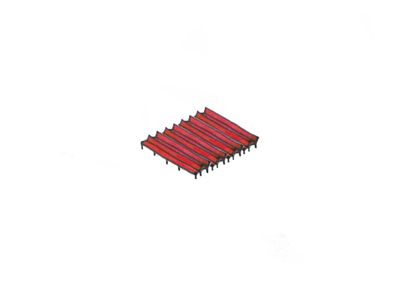

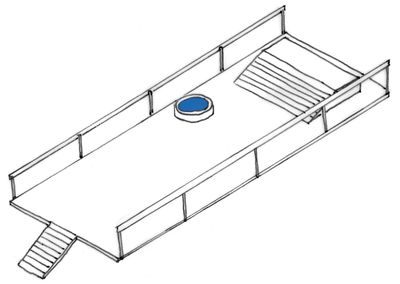

Andrea Branzi designed several movable architectural objects in a grid of pillars and transmitters. The podium and the platform with the rows of chairs allow a theatre-like configuration and thus a rare reference of social space embedded in agriculture. These are complemented by movable roofs and walls. The high shelf forms the interface of agricultural productivity as vertical farming and as storage for objects.

THE ARCHITECTURAL ELEMENTS OF AGRONICA

Source: Google Earth March 2023.

Rather than a project made to be actually realised, Agronica can be understood as a mental project, reflecting what the capitalist condition means for architecture and territory. But when looking at the Netherlands’ wide horizontal flat industrial agricultural fields, one is inclined to believe that Agronica and reality are not as far apart. What we can learn from this project is that agriculture is a legitimate part of the territory and connected to the city.

Yet, many practical questions and doubts remain. Who owns the land, who owns the means of production, who owns the products in Agronica? In the model, there are no enclosed spaces which might suggest that ownership does not exist, but Branzi does not explicitly address this in his text. With his proposed dissolution of hierarchies one could assume that the land is not owned by a single person, but collectively.

“Ideas count as much as facts do, indeed ideas are facts and hence produce, a change in the way of thinking, which to me is the central point.”—Andrea Branzi