AtlasKibbutzim: Common Work, Common Wealth, Common Land for a Common PurposeLeon Bloch, Viktor Jørgensen, and Roman Schürch

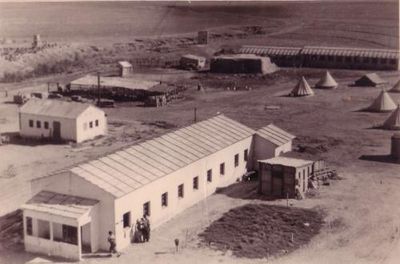

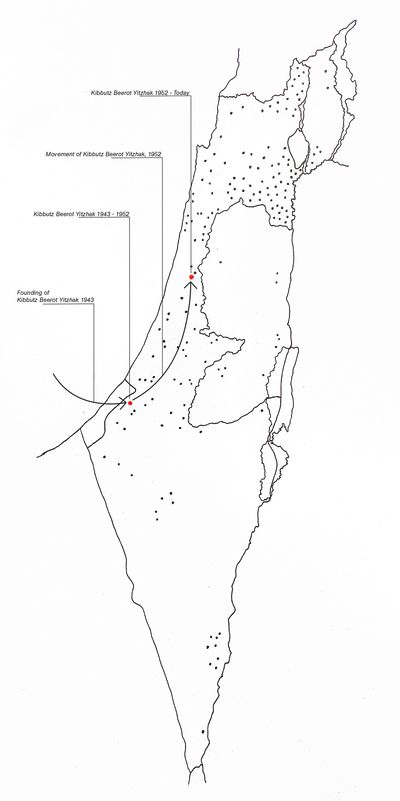

Kibbutz Beerot Yitzhak was founded in 1943 as a religious kibbutz by German immigrants in the Negev Desert southeast of Gaza. Like other kibbutzim, it was a project to build a community that would live on the basis of socialist and Marxist ideals of the collective. And like many other kibbutzim, it was also a political project: a step toward establishing Jewish sovereignty over the territory.

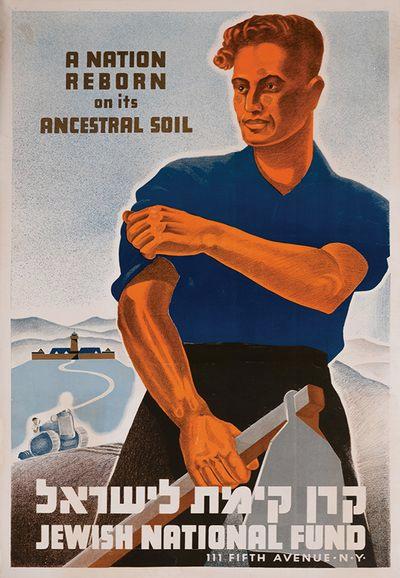

Kibbutzim, like Kibbutz Beerot Yitzhak, were created, founded, and settled by Jewish immigrants in the land that is today Israel, starting in the 1910s. Many fled persecution and pogroms in Europe and were searching for a new life. They were driven by multiple ideologies, mainly Jewish nationalism, Zionism, Socialism and Communism. The latter two can be traced from the fact that many of the original “Kibbutzniks” (Members of a Kibbutz) came from already established socialist or communist states in Eastern Europe.

A Kibbutz, which means “gathering” in Hebrew, is a community and settlement based on a collective living. Its inhabitants work in the kibbutz’ own agricultural and industrial enterprises and services to meet the needs of the community. However, kibbutzim have also a distinct political side: they are a way of colonising land.

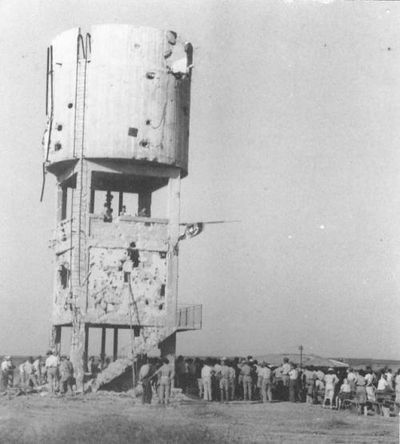

While the land of the first kibbutzim was bought off others, some were also built on land already belonging to people, or on land which was not officially owned by anyone. The early Israeli government used kibbutzim as part of the military campaign to conquer and control land areas. Settlements were built on strategically important areas and did sometimes have military infrastructure like watch towers included. This enforced the vision of Zionism/Jewish nationalism: To create a free state of their own in their biblical homeland on the former British mandate of Palestine. While military actions and wars were part of Israel from the very beginning, the settlements in form of cooperatives like the kibbutz were a unique way of securing this land. In 1989, the population of Israels’ kibbutzim reached its peak at 129,000 people living on more than 270 kibbutzim.

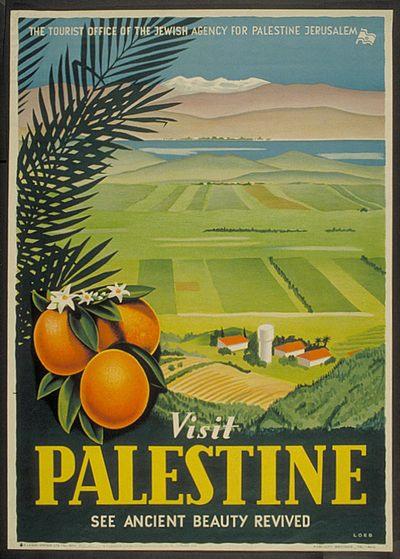

The promotion of kibbutzim was also a method used by the government to improve the quality of the land. In kibbutzim, its inhabitants re-cultivated land previously inapt for farming, transforming it into an “agricultural paradise.” Israels’ irrigated farmland has increased from 30,000 ha in 1948 to 460,000 ha today. In this way, agriculture became a celebrated part of the new country, also being heavily used in propaganda.

With the help of colonisation of land and a heavy industrialisation of production, 40 % of Israel’s agricultural and 9 % of its industrial production comes from kibbutzim, while only 2 % of the population lives there.

Source: Kibbutz Beerot Yitzhak, undated.

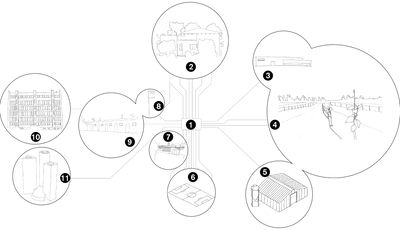

Source: Kibbutzvisit.

At Kibbutz Beerot Yitzhak, industrial production was one of the main sources for income. The inhabitants of the kibbutz produced pipes in a dedicated factory which were used for, among other uses, desalination plants near the dead sea. Additionally, an herb factory focused on preparing, mixing, packaging and distribution of mixed herbs and spices. The other main income source was farming and agriculture, focusing on corn and orchards like lemon, orange, or grapefruit trees, cotton, macadamia nuts, and avocado. The kibbutz served an animal farm with chicken, turkeys, and dairy cows. Even though agriculture was a big part of the life in the kibbutz, it did not result in much profit.

Like Kibbutz Beerot Yitzhak, kibbutzim had different agricultural practices and industry, depending on the location. Work would be divided in different factions. This could look something like this:

Of all the workers,

24 % worked in agriculture.

24 % worked in industry.

18 % worked in community services.

17 % worked in personal services.

11 % worked in tourism, commerce, and finance.

5 % worked in transportation and communication.

1 % worked in building and utilities.

Kibbutzim were structured around a spatial structure: Common facilities, such as the dining hall, kitchen, event locations, hospitals, and schools are in the centre of the settlement, creating a civic centre. Around them, housing was built. On the edges of the settlement, agricultural and industrial facilities, and the farmland were located. As a result, some kibbutzim became a town which had all economic sectors present right besides each other. Only in a few occasions, the inhabitants had to leave the kibbutz: for the rare occasions where someone would work outside the kibbutz, for certain educational facilities like high schools, or hospital stays.

At Kibbutz Beerot Yitzhak, the dining hall was the centre of the kibbutz; here everyone came together, during food breaks, after work, or for festivities. The three free daily meals, which were mandatory to attend as a general rule, included a large buffet for breakfast, an all-you-can-eat menu for lunch including different meats, soups, and vegetables, and again a buffet for dinner. As everybody was working, some did not bother to change out of their work clothes for eating or other common activities. This resulted in a distinct “Kibbutz fashion”, where work clothes and sandals became the norm.

Child care was organised communally. This meant that children were separated from their biological parents at a an early stage, as the women were needed in the workforce. Later on, this was abolished at Kibbutz Beerot Yitzhak, as it was in most other kibbutzim.

Most members were born in Kibbutz Beerot Yitzhak, grew up, went to school, married, and worked there, which resulted in a sense of local pride. In other words, everyone knew each other since childhood, resulting in close relationships. This had its downsides, as information and rumours would potentially circulate easily and quickly.

As Kibbutz Beerot Yitzhak was a religious kibbutz, the vast majority of the inhabitants were Jewish. Inhabitants were either full members of the cooperative, farm workers, or part of the “Ulpan” system. The latter allowed for young Jews from around the world to participate in a gap year, working in a kibbutz and learning Hebrew. Days were divided into classes in the morning and work in the afternoon.

When the first gulf war broke out in 1991, most members of the “Ulpan” system left. Those that stayed, became volunteers. As most young men were called into the military, there were less workers around to work on the crops. And so, the volunteers, many from abroad, took up that work.

Field work could mean 15 hours a day, 6 days a week in the hot sun. Some work required more work than usual, as for example: the cotton harvest, from ripeness to rain season, is short. So, the harvest is carried out in shifts, day and night. The macadamia nuts are very fragile, the plants complicated to access. This makes the harvest difficult, which at least returns a high selling price. Young trees need enormous amounts of care. Due to the climate, every tree has its own water sprinkler, and the irrigation system needs to be checked every day, to secure the functioning of the water supply. While kibbutzim had the perception of a new, utopian lifestyle, they required hard work to function.

Today, kibbutzim are in most cases no longer the communal project that they used to be. In some kibbutzim, land and houses were privatised and work was de-communalised. People began to also work outside the kibbutz, which resulted in monetary inequalities among the community. Other kibbutzim were transformed and opened by the community into tourist attractions where apartments are rented via Airbnb. Defenders of that transformation claim that in today’s globalised world, a strictly organised and controlled community life as it was in the kibbutzim does not fit the people’s needs anymore.

Kibbutz Beerot Yitzhak still has 470 inhabitants and has remained a cooperative. Different community projects encourage people to participate in common activities. Like in most kibbutzim, tourism has become part of the kibbutz’ economy: Kibbutz Beerot Yitzhak opens its dining room to the public, offers tours and operates a gift shop. With these transformations the kibbutz has also transformed spatially and visually. And objects such as a plow, once a necessary tool towards the reclamation and colonisation of land, have become symbols of an agrarian project for a territorial endeavour: the construction of the Jewish state.