AtlasPhalanstère: The Legacy of Charles Fourier, From the Palais Sociétaire to Today’s CooperativesSofia Gloor and Till Blaser

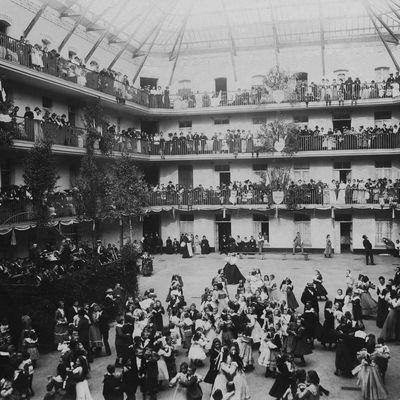

We are standing in the inner courtyard of the Familistère de Guise by Jean-Baptiste Godin (1817–88). Impressively, Godin stands there, as a bronze cast statue, sharing the moment with us. The building with its brick facade reminds us of the buildings of Red Vienna.

The Familistère functioned as a building to house a community until the 1960s. Parts of it are still inhabited today. The former farm shop now houses a coffee shop, the rest of the block is a museum. The theatre is still used for cultural events.

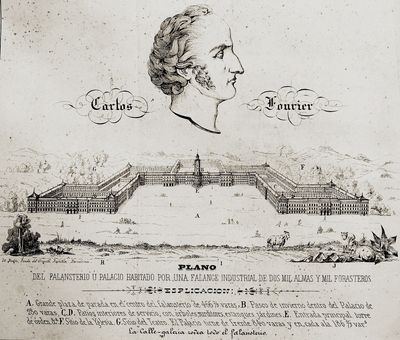

Godin’s Familistère is strongly based on the Phalanstère by Charles Fourier. Like his predecessor, Godin understood architecture as society-building. Fourier was a French philosopher, an influential early socialist thinker and one of the founders of utopian socialism. He is know as a radical thinker of his time and many of his social and moral views have become mainstream thinking in modern society. For instance, Fourier is credited with having originated the word feminism in 1837.

We go back in time, to the mid-19th century, when the Familistère was in its original use. The ensemble of the Familistère consists of three interconnected residential buildings, a nursery, a school, a theatre, and a factory. Inside the building: the atrium and the galleries—an important architectural element, a space to meet and mingle, that reminds us of Fourier’s ideas for the Phalanstère.

François Marie Charles Fourier (1772–1837) was a French philosopher and socialist thinker. In his writings, he declared that concern and cooperation were the secrets of social success. The Phalanstères or “grand hotels” where the structures for a “phalanx” (community) that could live these values. His social views and proposals inspired a whole movement of intentional communities—like the Familistère.

Fourier criticised the social order. At the centre of his criticism, however, was not the unjust distribution of social wealth or the suffering of the poor, but the hierarchy and waste. Fourier saw great potential in the community. Prosperity and health were the features of communal life and not the first goal. Social harmony, Fourier argued, was more productive, healthier and more pleasurable. Fourier proved this with a thought-experiment:

“Suppose a phalanx consisted of 400 families. Each family living separately would have a special kitchen to run. This would take up almost all the time of 400 housewives (…) In the phalanx, all the cooking is done in one enormous kitchen with three or four cookers on which dishes are prepared for different tables at different prices; ten experienced cooks do all the work, and the meals are infinitely better. The same is true of industry and agriculture.”

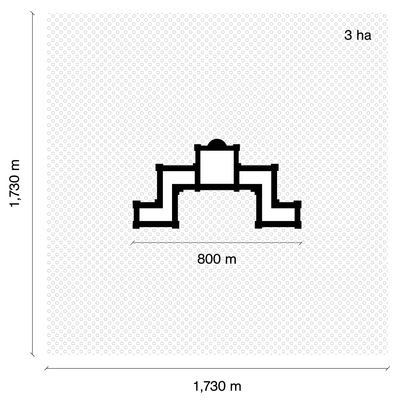

Fourier’s Phalanstère has the footprint of Versailles. There is a central building and two wings, each with a different use. Around it there is a three-hectares agricultural area that is cultivated by the residents of the Phalanstère. A total of 1600 people are supposed to live and maintain a Phalanstère.

In the courtyard parades and festivities take place. In the left wing there is the large kitchen of the Phalanstère. The children are brought up by the community and introduced to work at an early age. The children live on their own floor and are looked after by educators. The dining room is above and at the top there are the adults’ flats and spaces for visitors of the Phalanges. The centre is for quiet activities (counselling rooms, libraries). In the right wing there are the noisy workshops, the ateliers and the restaurant.

Fourier’s Theory of Human Passions: Love

Face

Hearing

Smell

Taste

Feeling

The first is the ideology of love. Fourier sees the concepts of face, hearing, smell, taste and feeling connected with it. Marriages are to be entered into, but entering into several relationships is part of the passions.

Fourier’s Theory of Human Passions: Family/community

Friendship

Love

Ambition

The second is the ideology of the family. Breaking up the traditional family structure is also supposed to support free love, but it also contributes significantly to increasing production. Keywords for this are friendship, love and ambition.

Fourier’s Theory of Human Passions: Work

Intrigue drive (cabaliste)

Variety drive (papillon)

Unification drive (composite)

Work is assigned irrespective of gender, but solely according to skill and talent. Men and women work side by side and in groups. Several groups form series that rotate in their activity. Fourier writes: “All human passions are justified and useful, and the ideal state of society is that which affords its members an unhindered opportunity for their gratification.”

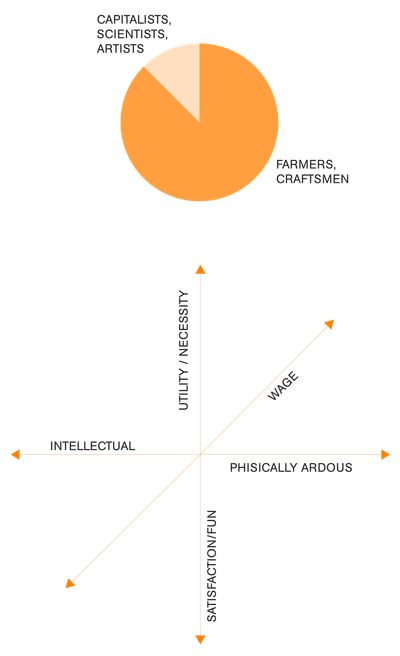

Wage and Value

Fourier does not propose a society based on financial equality, but what he calls a “compromise:” capitalism and individual property should exist, but basic needs such as shelter, food, work and community life are provided by the Phalanstère and are given to every worker, no matter what work they do. Special commitment, extra responsibility or an outstanding talent are paid extra.

“Neither jealousy nor antagonism is created by the distribution of profits, since there are no particular classes in the phalanx. One and the same member owns one or more share-certificates in the phalanx, works in one or more groups, develops a special dexterity in one or more branches of trade, and thus participates in all three classes of profit. On the other hand, the capitalist is either satisfied with the dividends on his deposit alone, or he increases them by the income he acquires by applying his labour or talent to some useful purpose.”

Fourier’s social structure reminds us of the unconditional basic income: “Those who find meaning and fulfilment in their work will work just as they did before. It is cynical, on the other hand, to insinuate that people do not know what to do with themselves and their time beyond work.”

Fourier upholds other values in the wage structure. Laborious and physically demanding work that is considered unpleasant is especially rewarded. Fourier reasons that the least attractive work needs the most incentive. Usefulness to the community is the second important factor. The more pleasant your work is, the less financial incentive is needed. Intellectual work is almost at the bottom of the wage structure and can only be pulled upwards by urgency. Fourier sees in particular farmers and craftsmen as essential for society, therefore seven-eighths of the population should work in these fields.

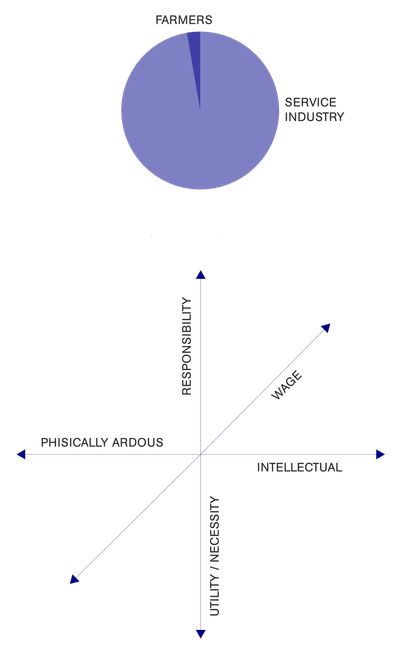

This is in stark contrast to the value system reflected in wages in the Western world, where intellectual work is highly valued and physical and care work is lowly valued. In the text A seventh man John Berger described it as follows: “The white collar offers membership of a higher division of labour. Higher because less physical. Higher because more abstracted. Higher because of the ‘sophistication’ of the equipment used.”

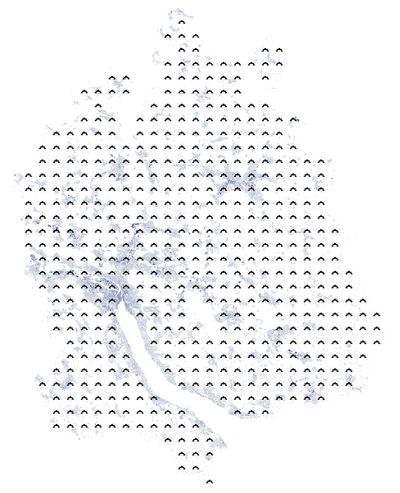

We were interested in understanding how the density of the Phalanstère typology compares with the Canton of Zurich: if Fourier’s grid of 800-metres-long Phalanstères and the surrounding farmland is laid over the area of Zurich, we arrive at a density of 59.7 % compared to the Canton’s current population density. It would take exactly 576 buildings. Most of the land between the built would be farmland, which allows for a more local food production.

With his Phalanstères, Fourier paved the way for housing cooperatives: for the Phalanstères, he proposed the inhabitants to become shareholders of the entreprise: “One and the same member owns one or more share-certificates in the phalanx (…)” Today, 21 % of residential buildings are cooperatives in the Canton of Zurich.

Some of Fourier’s ideas can also be recognised in recently built housing cooperatives in the Canton of Zurich, such as the Zollhaus in Zurich. Internal access corridors enable exchange among the residents, like in the Phalanstère. The building has a high density and diversity in use. The architects write: “With its diverse range of spaces for living, working, commerce, services, culture and community, the Zollhaus embodies a lively place that opens up to the neighbourhood and tests new possibilities for living together.” Fourier’s heritage is all around us.