AtlasThe Green Manifesto: Leberecht Migge and the Return to the LandAmélie Lambert, Nadina Häni, and Donata De Ieso

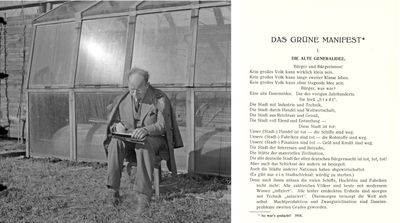

Bürger und Bürgerinnen!

Und so sehe ich unser neues Dasein

Sehe: viele kleine Häuslein—jeder Familie gehört eins.

(Neues Dasein verzehrt Ansprüche.)

Sehe: viele kleine Gärtlein—jeder Familie gehört eins.

(Neues Dasein vermehrt Früchte)

Sehe: natürliche Arbeitsweise—am eigenen Werk.

(Neues Dasein fordert Hand- und Kopfarbeit für alle.)

Sehe: kleinste Regierung—um der Regierten willen.

(Neues Dasein regelt sich selber.)

Sehe: höchste Erhebung—um der Erhabenen willen)

(Neues Dasein will Wallfahrt, Sonne und Spiel.)

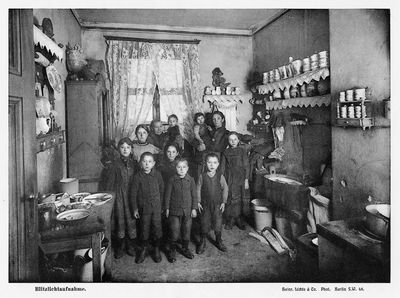

Leberecht Migge, gardener and landscape architect around the turn of the century, writes these lines in 1919 as part of his Green Manifesto. The landscapes and ways of living he envisions, families living in single family houses and working their productive gardens, are to be understood in the context of its time. Migge, born in 1881 and deceased in 1935, has lived in a period that’s marked by two important events: the industrial saturation and the First World War, which caused famine and poverty among large parts of the German society. The city became a place of precarity. People lived cramped and crowded because they could not afford appropriate places to live, as one of the consequences, illnesses spread easily. People left the city to live in the periphery, and only came back for work. During this time, other architects—like Howard or Unwin—manifested the urge to settle in the land, creating a new movement called Garden City, which later influenced Migge.

“Das Blut der Menschheit trank Vampir Stadt.”—Leberecht Migge, 1919.

During the revolutionary atmosphere of the abdication of the German Kaiser in 1918, Migge believes that a return to the land, which could drastically improve the living conditions of the German people, is possible, and he writes down his vision as The Green Manifesto. He imagines a land reform, which would allow families to settle in the countryside and overcome the City-Land divide. Each family would own a house with a garden to grow food. According to Migge, returning to the land will solve all the problems of the German population: The productive garden will make families independent of food prices and supplies, the work in the gardens will make them happier and healthier, and the possibility of reusing the waste in composting will make life more hygienic.

Leberecht Migge is an ambivalent figure; in “No House Building without Garden Building!” (Kein Hausbau ohne Landbau!) he describes himself as a “technocrat who provides the framework for a balanced life,” so we understand that technics is also a significant part of his thinking.

One of his central points is the intensification of the plots (Intensivierung der Grundstücke), which is achieved when each space is assigned a specific purpose and the plants are selected according to the specific conditions of their location.

Another concern for Migge is the reduction of waste. According to him, a waste cycle should be established to enable the reuse of (organic) material, in the form of compost, for example. This could ultimately also benefit the city, that would see a reduction in waste.

Leberecht Migge was also part of the Deutscher Werkbund, where artists and architects promoted and improved the design of mass-produced goods. The exchange with the members favoured the development of more architectural ideas as part of his vision: the settlement as the urban form for the return to the land, with a house unit and a garden for each family.

“Die Stadt darf nicht nur nehmen vom Land, die Stadt muss auch geben dem Land – will sie leben vom Land.”—Leberecht Migge, 1919.

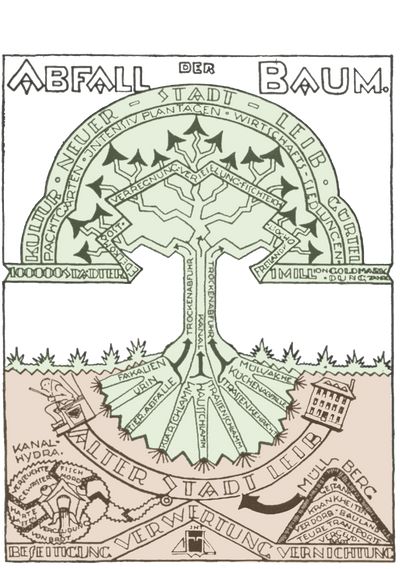

The scheme is divided into two parts: the first one, underground (red), represents the prevailing concept of the 19th century ("die alte Generalidee" ) where things out of use or sewage are considered waste, of which one must get rid. With a bad waste management, this results in the illness of the city dweller. The second part, above the ground (green), represents the new concept for the city of the 20th century ("die neue Generalidee") with a closed nutrient cycle and the introduction of recycling, which will ultimately make the tree grow and allow for fresh air.

Source: Leberecht Migge's "Green Manifesto": Envisioning a Revolution of Gardens, Haney.

Everyone Self-Sufficient!

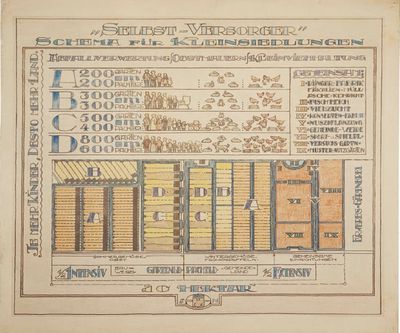

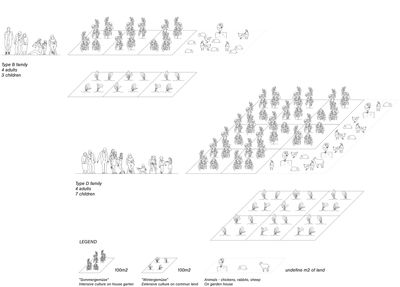

In the book Jedermann Selbstversorger! (1918) Migge describes in detail how the life and gardening on the countryside could look like. He advocates for self-sufficiency regarding food. The garden should therefore have the necessary surface to to meet the family’s nutritional needs. In the book, he makes a precise calculation of the surface needed depending on the size of the household. In addition, Migge proposes a scheme of where what kind of cultivation should take place. For the summer vegetables (Sommergemüse) he proposes a piece of land close to the house, because it is a laborious cultivation which requires intensive care. The winter vegetables are cultivated extensively, this is why they are cultivated on the communal fields outside of the private garden. The communal field is a piece of commonly used land, where every family has a plot whose size depends on the size of the household. Animal farming, for which Migge proposes exact numbers, takes place in the private gardens.

HOUSE AND GARDEN AS ONE ORGANISM

Sources: No House Building without Garden Building!" ("Kein Hausbau ohne Landbau!"): The Modern Landscapes of Leberecht Migge, David Haney, University of Pennsylvania; Leberecht Migge's "Green Manifesto": Envisioning a Revolution of Gardens, Haney.

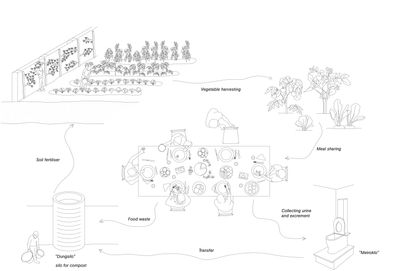

The garden should be allocated on the Southern side of the house. The dry toilet (Metroklo), that allows the collection of urine and excrement, is an annex to the house in proximity to the garden. Next to the toilets there is a winter garden, where the plant pupils are grown, in order to benefit more from the sun. The dung silo (Dungsilo), a container to store and transform organic waste into fertiliser, is located at the southern end of the garden. The presence of plants outside of the garden itself—such as the wild wine that grows on the walls of the house and around the garden (Schutzmauern)—reveals another aspect of Migge’s thinking: efficiency. An underground pipe transports the waste water from the house (shower, kitchen) to the garden.

The Life in a Garden House

After coming home from work, the family gathers to work in the garden, watering the plants, harvesting vegetables. The son uses the dry toilet, where his excrements are collected. For dinner, the mother prepares a meal with the harvested produce. The organice waste is collected in the Metroklo as well and will later be transported to the dung silo to be used again as fertiliser for the cultivated land.

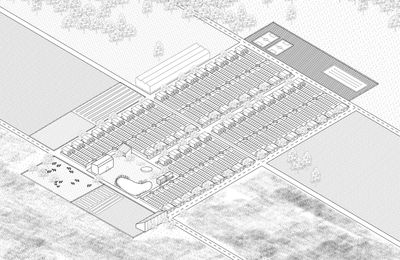

Knarrbergsiedlung Dessau-Ziebigk

In addition to designing schemes of garden houses, Migge was also interested in the urban form of a settlement of garden houses. The plans he developed, often in collaboration with architects, followed the principles of the Garden City. His proposals included, on the one hand, terraced houses with productive gardens, on the other hand, communal spaces with sport fields, fish ponds and other commonly cultivated areas. The housing estates were accessed by avenues lined with fruit trees. The buildings’ construction should be simple and functional, allowing prefabrication and mass production. Also on this larger scale, Migge’s paradigms of productivity and efficiency come across.

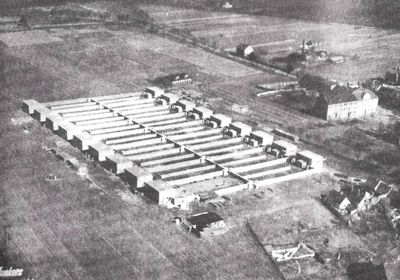

The Knarrbergsiedlung in Dessau-Ziebigk (1926–28) is one of the housing estates Leberecht Migge realised in collaboration with the architect Leopold Fischer. The settlement was commissioned by the Anhaltische Siedlerverband in view of the acute housing shortage in Dessau. The design for the settlement comprises semi-detached houses with large gardens, a communal square and avenues. Common productive spaces like fish ponds or the communal fields for extensive winter vegetables, that Migge had conceived in his theoretical work, are missing in the design.

Leberecht Migge’s aim was to free people from the precariousness of the city by returning to the land, as he proclaimed in The Green Manifesto. But the exploitative conditions of the urban realm he criticises seem to reappear in his vision. This becomes apparent in the language he uses to describe the new life on the countryside: “Mehr Arbeitskraft durch Maschinen” or “Intensivierung aller Landwirtschaft” (The Green Manifesto, 1919). Migge aimed also at establishing a new connection between the countryside and the city. When looking at the Knarrbergsiedlung, a design that is urban in many ways, it seems like an unbalanced relationship, that suggests rather the domination over the countryside through the urban form.

Finally, Migge’s proposals built solely on the core family with healthy and apt members to do farm work. But what about other types of households and sick or elderly people? What happens when a family member or the children leave the house? Migge leaves these questions open.

Despite these criticisms, Leberecht Migge’s proposals, such as the closed waste cycle within a house and the question of the relation of the urban dweller to the land and food, can be considered even today as highly progressive ideas, we can still learn from.