LabourConducting Human Resources: Migrant Workers in SingaporeAhmed Belkhodja and Saskja Odermatt

The mixing of ethnicities and migrant labour have been enduring characteristics of Singapore’s population. When the country became independent in 1965, most of its new citizens were uneducated immigrants from China, Malaysia and India. Many of them were seeking to earn some money and had no intentions of staying for good. After the independence, the process of crafting the new national identity began. The former prime minister Lee Kuan Yew stated that Singapore does not fit the traditional description of a nation, calling it a society in transition. Singapore’s population continues to be highly mobile, multi-ethnic and global in character. According to the recent census, it consists of 74.2 % Chinese residents, 13.4 % Malay, 9.2 % Indian descent residents, with Eurasians and other groups forming 3.2 %. The present population of the country is around 5.18 million people, of whom 3.25 million (63 %) are citizens, and the rest (37 %) are permanent residents and foreign workers.

It is fascinating that Singapore’s economy continues to depend on imports of both labour and inhabitants. Nearly half (47.9 %) of the Singaporean workforce is comprised of foreigners, and this number is expected to increase due to the decline and ageing of the resident population. The government estimates that 30,000 migrants per year are needed in order to maintain the constant size of the country’s workforce; the actual immigration statistics in the past decade confirm these projections.

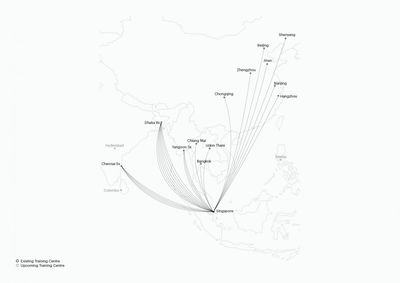

More than one million foreign workers currently in Singapore, from a relatively heterogeneous group. A smaller proportion belongs to elite professionals, the so-called expats, but the majority (nearly 900,000) consists of low-wage workers, especially the construction workers and domestic helpers. This part of the workforce originates from countries in the region, including Malaysia, Indonesia, China, Bangladesh, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam.

Elaborate transnational systems of workers’ recruitment form an invisible structure behind the foreign workers’ presence. Various protagonists play a role in this system, starting with local recruitment and training agencies, to employment agencies in Singapore.

The temporary working contracts (usually with two-year duration) and high commissions that workers pay in order to enter the recruitment process, are illustrations of employment regulatory systems providing high security for both the Singaporean state and the employing firms.

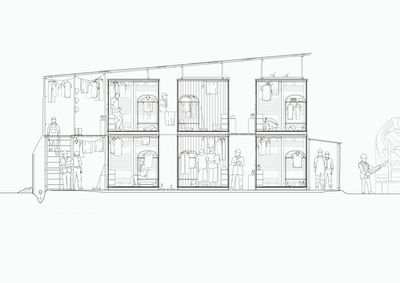

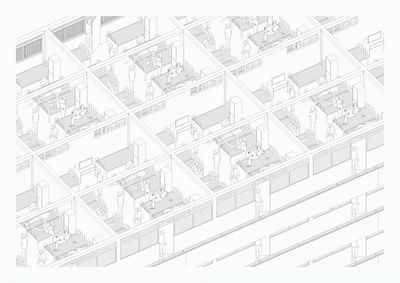

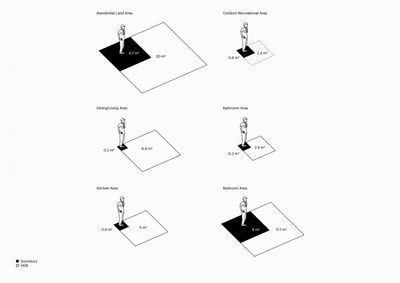

The political consequences of foreign labour are not to be underestimated. While attracting foreign talent has been important for Singapore’s position as a global city, immigration and income inequality have also emerged as pressing issues. The need to strike a balance between openness and local concerns presents one of the most critical political challenges for Singapore. The sensitive problematic of the foreign labour is perhaps best understood by looking at urban spaces of foreign workers and their relation with the rest of the city. Even at first glance, a separation of spaces of resident and foreign worker populations is noticeable. In the case of foreign construction workers, a separation of living, working and socialising spaces, along with exclusive means of transport and various services, such as the ATM machines, reinforce a perception of parallel urban spaces, carefully kept at a distance from the rest of the city through planning and regulatory instruments.

The goal of the work was to shed light on the complex phenomenon of transnational work migration in Singapore, and to investigate and describe the architectural, urbanistic and social characteristics of spaces in the city used and adapted by the foreign workers.