FisheryCultivated Sea: Fishing and Aquaculture in a Metropolitan RegionSimone Michel and Anna-Katharina Zahler

Traditionally, fishing has been one of the main economies in the region. Older generations of Singaporeans remember the schooners of the Makassar Bugis docking at the barter trade center in Pasir Panjang, the local gathering point for boats from all over the Indonesian archipelago, where the trade of fish, sea cucumber and other foods and small goods flourished into the 1980s.

Different factors brought modernisation to the traditional fishing and food economies and cultures. From the mid 19th century, steamships enlarged the scale of fishing and fish trade. Singapore was an important fishing harbour where products were sold and distributed to the Malayan hinterland via railway and roads.

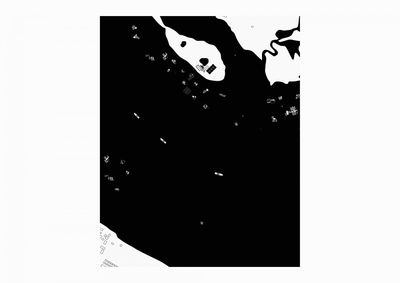

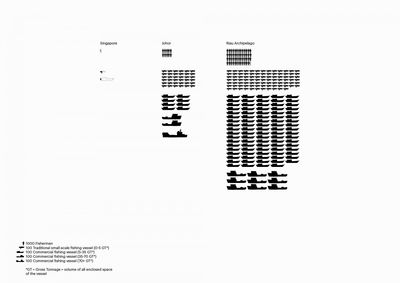

In the industrial society, eating habits gradually changed too. Fresh fish and canned fish replaced the dried salted fish. Growing populations all over Asia introduced the need for cheaper food; poultry for example replaced marine products as major source of animal protein in the diet of the region’s population. It is estimated that in the early 1980s, 75,000 people were still fishing on the Straits (70 % Indonesian, 27 % Malay and 3 % from Singapore). In the late 1980s, Singapore opted to phase out most of its agricultural production. Today the city imports 95 % of its food, and only 3 % of fish consumed in the city comes from local farms and fishing grounds. The production of ornamental fish for export in several agro-technology parks today actually exceeds the sustenance production.

The fish arrives to Singapore from long distances; from Indonesia it is shipped by carrier vessels, from Malaysia and Thailand it sometimes comes by lorries. From the countries further out such as Norway, the fish arrives by plane directly from the airport to the Jurong Fishery Port before being distributed. Large-scale commercial fishing is now present in the region alongside local and traditional fishing and sea farming. Motorisation of boats pushed the frontiers of the former fishing grounds into deeper waters; this requires larger vessels, larger ports and cold storage facilities, and implies a high degree of regulation and bureaucracy. These infrastructures, together with massive supply and distribution networks, usually give large-scale commercial fishing advantage over fish from local production. In this manner commercial fishing practices often results in destruction of local fishing economies and markets.

After 1965, the regional fragmentation to national territories led to weakening of trading networks. In 1981 for example, the Indonesian authorities confiscated 16 fishing vessels from Malaysia and observers of the event noted that “to be caught fishing in Indonesian waters entails the risk of losing boats, gear, the day’s catch, or even life itself.” Until today difficulties with taxation and declaration of goods in the cross-border situation prevent or reduce the flow of catches from Riau to Singapore, or foster informal trade under false declarations. Additional issues such as land reclamation, the heavy shipping traffic in the Straits and the discharge of chemicals, puts the marine environment in the region under pressure. Since the 1970s, aquaculture (and fish consumption) have grown tremendously and many commercial fish and prawn farms can be found off the coastline of the Strait of Johor. This type of farming also poses environmental hazards as it often involves removal of mangroves and water pollution.

Traditional fishing communities are still mostly active in Riau. In Batam municipality, traditional fishing continues to form an economic base for about 5 % of the population (in 2010, 9487 households were active in the fishing, compared to only 1758 active in agriculture). These are communities whose daily lives and practices are already in the gravity vortex of the nearby cities. Possibilities to preserve or integrate their cultures and ways of life into modern urban economies in the region have so far presented unsolvable equations.

The goal of the work is to examine potentials for tri-national fishing and aquaculture in the region that would be able to meet the local needs. The project explores the advantage of cross border planning strategies: ways to ensure high water quality and ecological quality of the marine environment, and ways to create local territories for fishing and sea farming in balance with other functions of the maritime space. The project also discusses cross border approach to regulations concerning the production, distribution and trade. The project provides arguments for the productive role of fishing and mariculture, in their ability to raise appeal and quality of life in the cross-border metropolis, and explores ways in which they can be seen as an element of region’s identity and cultural heritage.