HeritageMemory Archipelago: Living Heritage in the Sea RegionManuel Crepaz and Martino Iorno

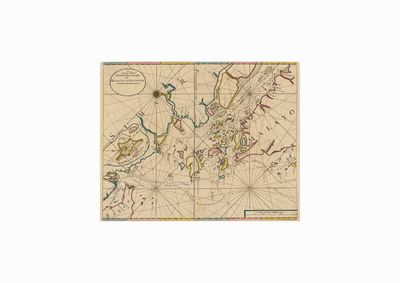

Pulau Ujong, the Malay transliteration of the Chinese Pu Luo Chung, named Singapore as the “island at the end” already in the IV century. Geographically, Tanjung Piai in the west of Johor Bahru marks the southernmost point of the peninsular Malaysia and of the Asian continent. From here, the Asian mainland dissolves into the 18,307 islands of the Indonesian Archipelago.

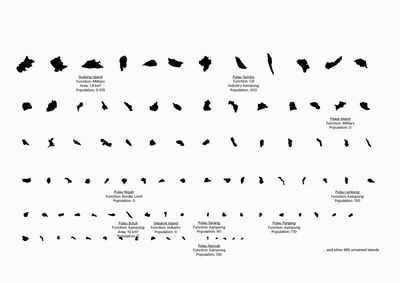

The roughly 2,760 inhabited islands in the Johor, Singapore and Riau region can be described in terms of their traditional archipelagic culture in which settlement structures used to stretch along the coast, and economy and daily life gravitated towards the sea. Few hundred other islands in the archipelago are uninhabited and covered by vegetation. At the same time, the archipelago is a site of conflict imposed by urbanisation, the reshaping of landscape for infrastructures, industrial zones or tourist facilities.

Islands and coasts in the region are places of memory, as most traditional settlements are located along the coast and in the river mouths. Calm and shallow waters of the archipelago, safe anchorage places and rich fishing grounds have always attracted settlers. Settlements along the Johor River leading to the hinterland were of great importance; this passageway to the interior had even attracted the Portuguese fleet to sail beyond Kota Tinggi in 1535. Next to the indigenous Malay, diverse ethnic groups from China, Mongolia, Thailand and Java settled in the region. From the 16th to mid 19th century, in the period of international maritime trade and warfare known as the Age of Sail, the Europeans arrived in the region and founded their ports. These continuous migration flows and cultural crossovers in the archipelago have created a specific cultural heritage.

Not many sites of history and memory in the region are known and accessible. Due to their often remote locations on small islands, they are removed from public view and semi-forgotten. The preserved heritage sites include for example the Raffles Lighthouse, the Kusu and the Sister’s islands, and the Penyengat Island, with its mosque, the former fort and the residence of the sultan ruling over the Malay-Bugis Kingdom in the late 18th century. Other sites such as the Fort Canning Lighthouse and the Long Ya Men rock have been rebuilt, occasionally even in a different location. The quarantine station on Saint John’s Island, the recreational facilities on Pulau Damar Laut, and schools and cemeteries on other Southern Islands have been lost.

In Riau, there are areas and relationships that are exceptional in the fact that they still convey the more traditional form of archipelago culture. Here, children take boats to the next island to reach school, mosques are the places of public life even on the smallest of islands, houses are built on stilts on the shore and boats connect between island communities.

The future of these island communities in the archipelago is uncertain; they are already to various degrees subsumed in the urban economy and dependent on modern infrastructures and services. Their incremental growth would be desirable, but they often fall victim to industrial expansion and tourism. The shift from traditional archipelagic culture of settlements focused on the sea, to the modern land-based thinking and urban development, has made life on mainland more attractive. The heritage of the archipelago should thus be seen as the specific asset for the region’s culture and identity.

The goal of the project has been to explore a common vision for preservation of the maritime culture of the tri-national region, by curating sites of memory in the archipelago.