TransportSea Transport: Passenger Mobility in the Sea RegionSarah Barras and Benjamin Blocher

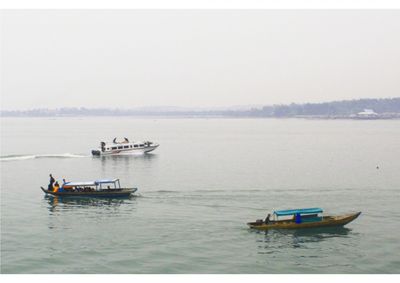

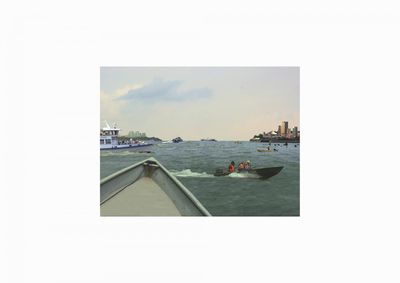

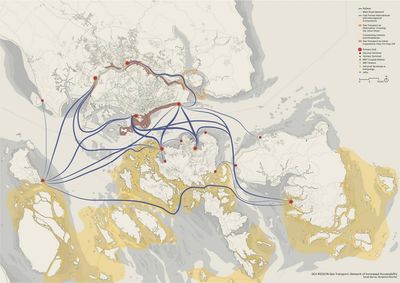

The Singapore, Johor and Riau region has a rich tradition of water transport. Though land-based forms of transportation steadily grew and became predominant during the 20th century, people still move by sea. High-speed ferries connect the local and the regional ferry terminals and harbours into a relatively dense network. Singapore Tourism Board reports that in 2013, more than 1.5 million visitors arrived in Singapore by sea; more than half of all arrivals, around 70,000 per month, were from Indonesia. Similar numbers were reported for Batam: nearly 70,000 Singaporean and 23,000 Malaysian visitors arrived at the island by ferry in February 2013. Looking at the seascapes in the region, one can observe great differences in the use and types of boats. Huge air-conditioned ships dominate the international shipping fairways and the anchorages of the Singapore port, while in other parts of Singapore and Johor people still move by bumboats. Chinese sampans move among the islands in the Riau Archipelago.

The technological changes have radically transformed the nature of sea travel, and had great impact on the shape and function of ports and cities. The period from the 16th to the mid 19th century in Southeast Asia and the world is known as the Age of Sail; human migration and international trade from the Arab world, India, China and Europe reached Singapore and the region by sailboats. During the first half of the 19th century more efficient steam ships and ocean liners gradually replaced sailboats, and subsequently other new techniques and technologies continued to transform the nature of sea transport.

Among the most important, the “containerisation” of the 1960s was a logistic revolution that enabled globalisation and escalation of cargo shipping. Around the same time, with the advent of air travel, line voyages nearly ceased to exist. These changes also revolutionised the character of the port and its interaction with the city. In Singapore and other port cities, this has been a movement from the times when port and waterfront presented commercial and cosmopolitan centres, to the present day when the port and the sea have became logistic territories at the periphery of public perception.

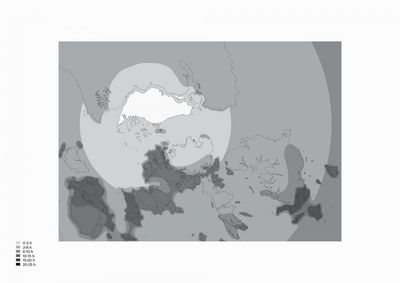

Political history of the sea region is equally crucial, as it gives an insight into the changing nature of maritime borders. The colonial period was marked by a bipolar political geography in the region: after the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824, Riau Archipelago was controlled by the Dutch with their port in Tanjung Pinang, rivalled by the British in Singapore and Johor. The flows of goods in the Singapore Straits were highly regulated at the time, but people moved freely from coast to coast. There were no passports; ferry connections between Johor Bahru and Singapore as well as Singapore, Batam and Tanjung Pinang where frequent, and small boats could be rented for shorter distances and travels across the Strait.

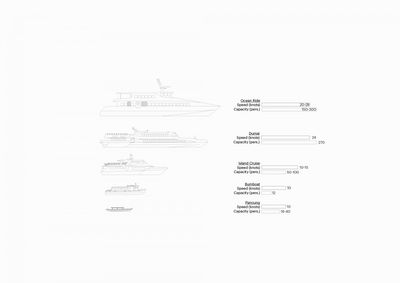

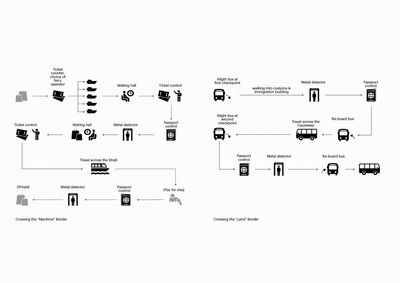

With the events of the 1963-66 Confrontation and of Singapore’s independence in 1965, the fluid character of the border was replaced by attempts to establish national sovereignties over maritime space. The gradual introduction of national borders also reflected in new ways of water transport. The flexible, small-scale boats were replaced by large-scale, directional ferry connections. Today’s ferry terminals function as intermodal interchanges, immigration checkpoints and commercial centres (with shopping malls, casinos, etc); they generally have no public waterfront. The immigration control procedures—the fingerprints, passport scans, check-in and boarding, etc.—have added to the formalisation of the water transport. The ferries follow fixed routes and cross the international shipping fairway on designated crossing points. With a capacity of up to 250 passengers, they travel at speed of 28 knots (50 km/h). They serve different uses, from business to weekend leisure trips. By contrast to the increasingly rigid patterns of public movement across the Straits, the transfer of goods in the region was simplified through the introduction of special economic zones—the new “borderless” territories and free-flow regimes of globalised production and trade. Thus, in less than fifty years since the independence of Singapore, the character of movement across the sea in the region has been reversed: from a flexible and open transport based on smaller boats, to an increasingly rigid and directional type of movement.

The goal of the project has been to explore possibilities for a new model of water based public transport in the tri-national region. The specific interest has been in the possibility of small scale, flexible connections (smaller boats, longer waterfronts, flexible embarkation and disembarkation) that could complement the existing transport networks. The project provides arguments for the productive role of water transport for the region, in its ability to raise appeal and value of living, work and leisure in the cross-border metropolis. The project explores ways in which water transport can be seen as an element of region’s identity and cultural heritage.