AtlasGasFilippo Biasca-Caroni, Martin Kohlberger, and Isidor Gonzalez Escobar

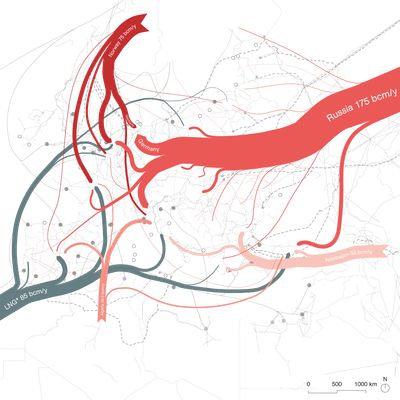

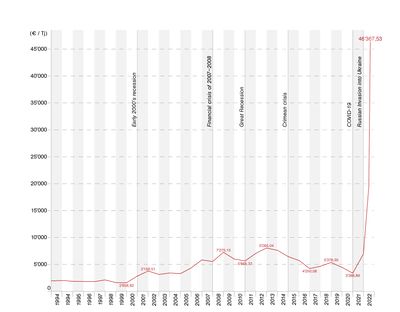

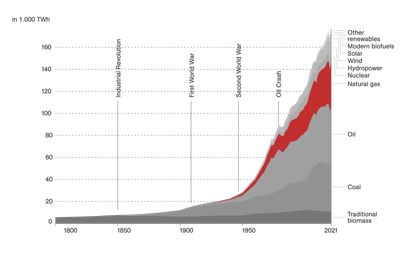

While German state leaders have carefully built up the energy supply on the Russian gas over the last century, the news on the interruption of the European gas supply by Russia have put Europe in a state of shock and fear. Triggered by Russia’s war in Ukraine, the fragility of Europe’s gas supply and especially Germany’s dependence on Russian gas is becoming increasingly apparent. Already starting in February this year, following Russia’s war on Ukraine and the subsequent EU sanctions—in combination with the world economic impact of Covid19—the European gas prices have spiked. Today, they are more than eightfold the price of what we were used to pay some years ago. In the summer of 2022 many European countries still might have been able to get their hands on gas to fill their gas reserves, but already next year this might become difficult. What does this mean for the gas network and for how heating will evolve?

Under Pressure: Gas Supply and National Interests

Source: Comet Photo AG (Zürich), 1973

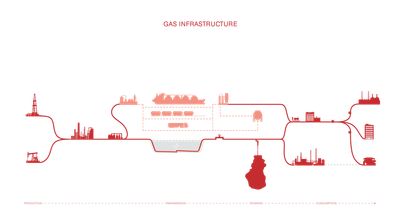

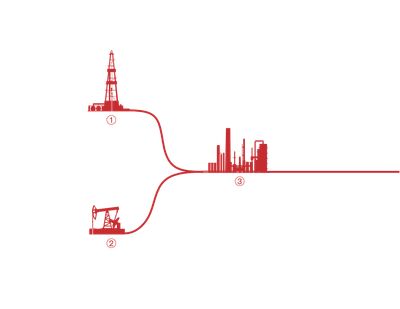

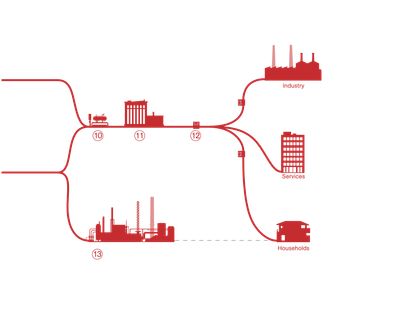

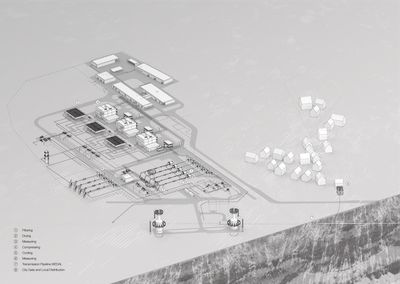

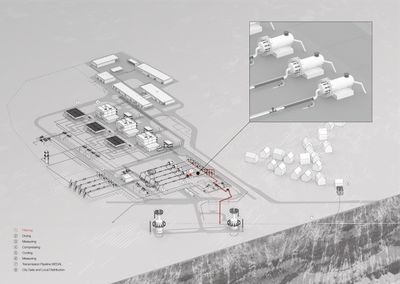

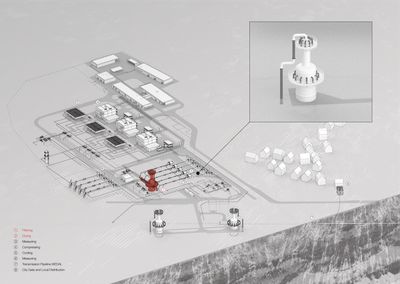

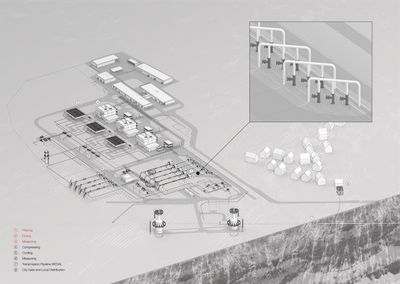

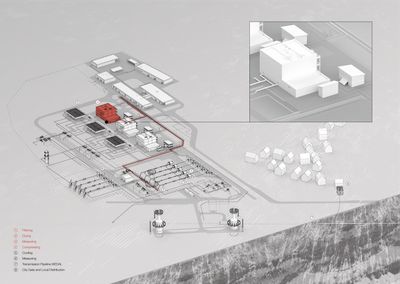

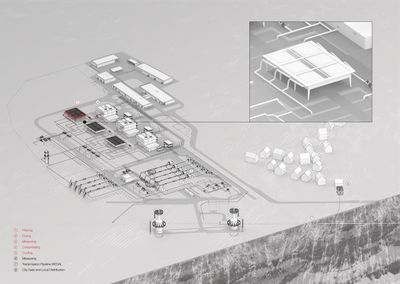

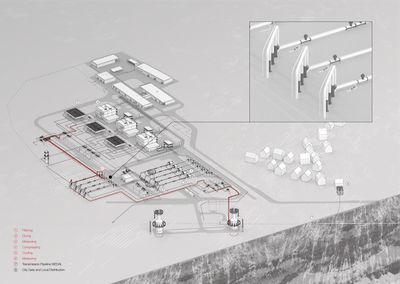

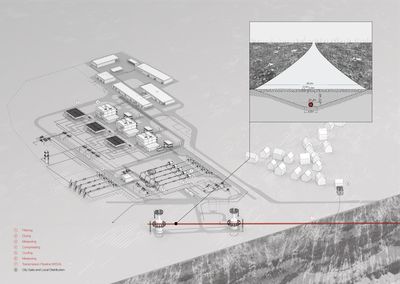

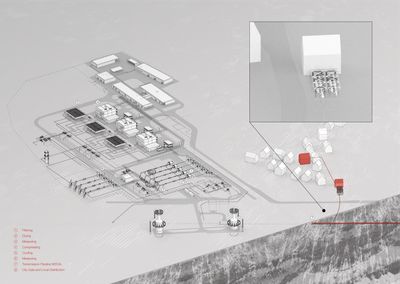

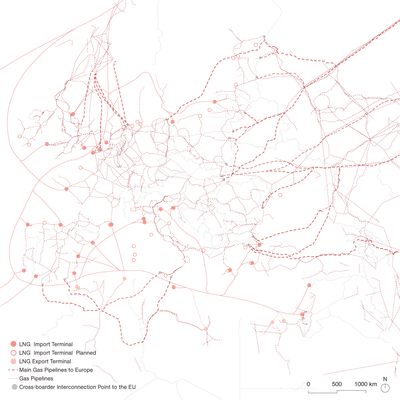

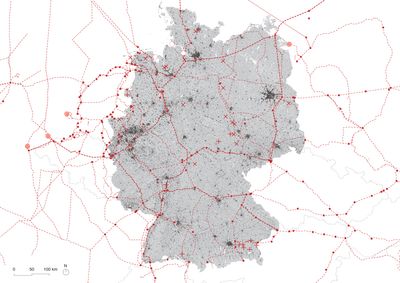

Unlike the global scale of oil markets, the European gas infrastructure is currently a continental interconnected system, with gas flowing from the extraction sites in resource-rich countries such as Russia, Norway or Qatar to our building (Long, 2004). From extraction to consumption, an interruption at a single junction of this interlinked system of pipelines can have major consequences. In order to ensure the flow of gas, the network requires a number of facilities in addition to the pipelines themselves: be it the gas metre in our own building, the so-called city gate, which is responsible for the transfer to the local network, or the compressor stations, which generate a gas pressure of up to 27.5 bar to propel the gas through the transmission pipelines and are arranged approximately 100 kilometres apart. The smaller local lines starting at the city gates and serving the settlements, are working on a much lower pressure.

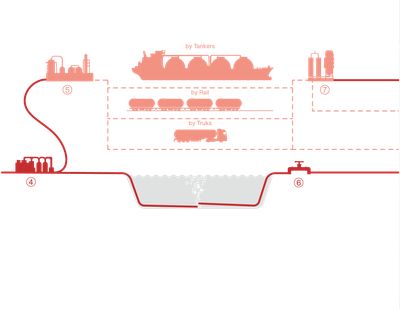

The national gas supply also includes the much-discussed cavern or pore gas storage facilities. In order to fill them in the upcoming years, recent ideas have popped up to include more terminals and facilities for liquified natural gas (LNG). By that, gas would be made shippable just like oil and would not be bound to the rigid pipeline network anymore. In parallel, there are attempts to import from a more diverse number of supply countries such as Azerbaijan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Algeria, Israel and the USA. But will the solution to the gas crisis be that Germany is now dependent on five partner autocracies instead of one?

The Geopolitics of Gas: Constructing New Dependencies

Source: Comet Photo AG, 1973

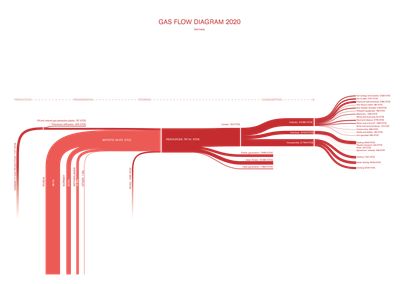

After Russia launched the war on Ukraine, gas quickly became a means of a trade war with huge price increases in response to European sanctions. Since February, it has become clear that the dependence on Russian gas has no future for Europe and specifically Germany, where Russian gas accounts for 66 percent of the country’s energy supply in 2020 (Eurostat, 2020). However, not only the current crisis is the problem. Energy and gas supply generally depend on fragile arrangements and treaties between individual states. Focusing on the interest of their own economies, the states act in the words of Friedrich Engels as the “ideal personification of total national capital” (Engels, 1880, p. 222).

Germany concludes treaties and national agreements with despotic leaders and totalitarian economies that oppress their populations—just like Qatar who recently made news with the inhumane working conditions on its building sites. These agreements not only interweave into a network of economic and legal dependency, but are entrenched in the material infrastructure of the gas network that has been built and expanded over decades.

Source: Global Energy Monitor, 2022

Source: Eurostat, 2020

GERMANY’S GAS INFSTRUCTURE

Source: Global Energy Monitor, 2022, and ENTSOG, 2019

Gas pipeline

Gas pipeline Compressor station

Compressor station LNG import terminal

LNG import terminal LNG import terminal planned

LNG import terminal planned Aquifer gas storage

Aquifer gas storage Salt cavity storage

Salt cavity storage Depleted gasfield storage

Depleted gasfield storage Other storage types

Other storage types Urban structure

Urban structure

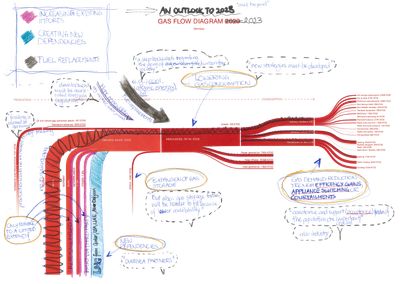

What will the gas supply look like in the future? Currently, many European states are eager to negotiate with other gas-producing countries and to switch to LNG, brought by ship from countries such as Norway, Algeria, Australia, Canada and the U.S.. But LNG will not be able to replace the amount of Russian gas in the long run, let alone short-term (Energy Intelligence, 2022). The NGO Greenpeace is extremely sceptical about the propagated possibility of later repurposing the newly planned LNG-terminals for hydrogen—this has simply never happened before and would require completely different facilities (Bukkold, 2022, p. 43).

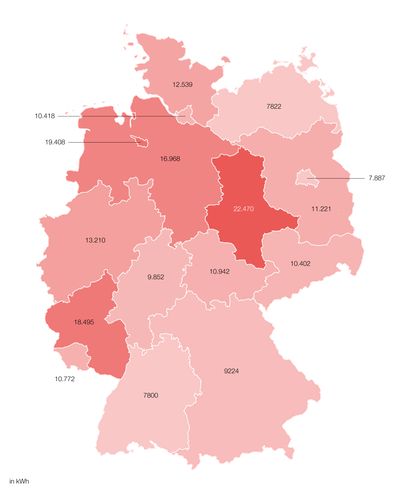

Source: Statistisches Bundesamt, 2022

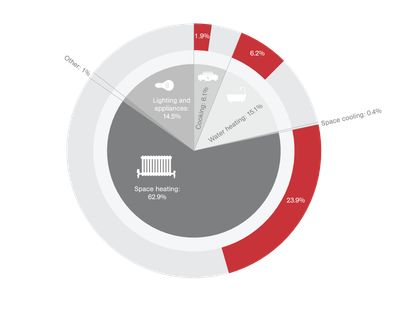

Gas prices have been rising rapidly in recent months. Even though they are now easing somewhat, prices are still higher than most can afford, especially for gas, 30 % of which is used for household energy consumption and thus has a direct impact on individuals. In Germany, the per capita consumption of gas is particularly high, partly because of the high gas consumption of German industry.

-162°C Or How to Keep Yourself Warm with Cold Gas Lines

Source: Hans Witschi, 1973

31 % of gas is consumed by private households (BDEW, 2022). Current price spikes make heating an expensive endeavour for gas-fired households, which hits the poorest hardest. So far it has been difficult to secure prices because Germany’s gas network is fragmented among private players. The nationalisation of the insolvent gas network operator Uniper and the recently introduced German gas price cap solve this problem for the time being. However, it brings hardship to other European countries with lower budget reserves, such as Slovakia, which cannot keep up with such enormous programs (Tooze/Abadi, 2022). Experts such as the internationally renowned economist Adam Tooze predict an extreme distribution struggle between individual European countries, leaving the economically stronger states on top while the others will fall short.

In recent years, the German state has invested in pipelines connecting Dutch LNG terminals with the German network, in order to secure the cheap gas supply in Germany. “Zeelink” is one of these projects, with a newly built compressor station in Würselen, Germany. However, as LNG has to be cooled to a temperature of -162 °C, it is far less CO₂-efficient than conventional gas, and the conversion of power plants will take years.

Both ensuring energy supply for heating in Germany and reducing carbon emissions seems incompatible in the face of the current gas prices. But for a more just and ecological future, new forms of heat and energy supply must be developed and monopolies in the energy industry broken up.

Source: Vaclav Smil, 2017, and BP Statistical Review of World Energy, 2022

Source: Google Earth, 2020