AtlasFuture FarmsJeffrey Barman, Hassan Ayaz, Tamino Hertel, and Zan Kocunik

Over the past century, agriculture has transformed vastly due to modern machinery, desired product output, and societal structures. Our study of farmhouses in Zurich North reveals the impact of these changes on the architecture, local image and ways of living. The majority of the buildings on our site are located outside of the building zone. Instead, they are spread all over the agricultural zone, where they are subject to strict building regulations and heritage protection laws. Combining this framework and a decreasing number of active farms and farmers results in abundant empty structures. In the near future, planners must aim to repurpose them and develop their potential. Notions such as social life, affordability, and infrastructure will be essential.

Stories from Zurich North

A Snapshot of the Status Quo

Across the vast expanse of Zurich North (7,340,000 m2), 24 farms mark the landscape. The area is characterised by 186 structures for farming purposes and 231 residential buildings. Despite many of the buildings being officially classified for farming, the analysis on the field revealed the actual situation of Zurich North. A significant number of agricultural structures were repurposed and used as warehouses. Others stand vacant, falling into ruins. Several factors contribute to this phenomenon: their position on the agricultural or core zone (Kernzone), modern agricultural machinery, rigid and demanding heritage protection laws, and the lack of subsidies.

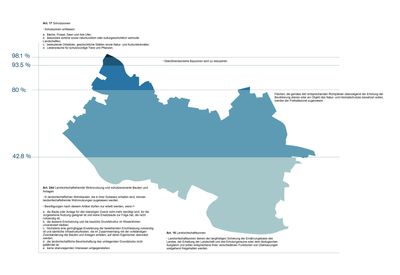

Remarkably, just 5.5 % of our landscape belongs to the building zone and is thus permissible for building and development. The rest of the area consists mainly of the agricultural zone and reserve areas, which must be preserved and protected according to the state and cantonal guidelines. This strict preservation of agricultural land can be counter-productive as it limits the growth and modernisation of farms. A valuable part of the area is the core zone, which aims to preserve the settlements’ character. In contrast to the agricultural zone, building, upgrading, or replacing within the zone is permissible as long as it meets the extensive heritage protection criteria. This usually results in costs that local farmers can not meet.

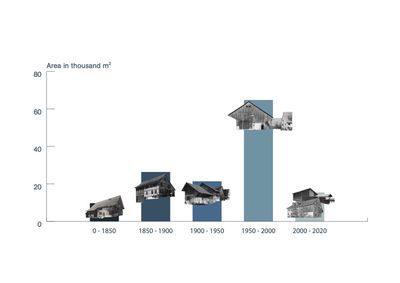

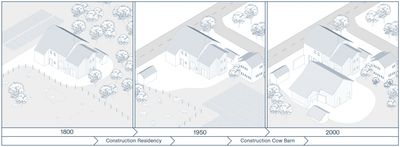

The majority of the site’s development happened in the second half of the 20th century. However the area is also marked by many old buildings dating back to the 19th and 18th century. These structures survived due to their capacity to adapt and are now the subject of heritage protection. In the 21st century, strict laws and guidelines impacted the growth and development of the area and set many challenges for today’s farms located in Zurich North.

Zurich Farmhouse Typology—A Model to Adapt

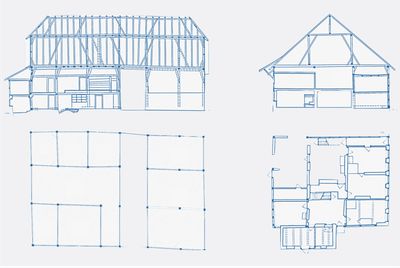

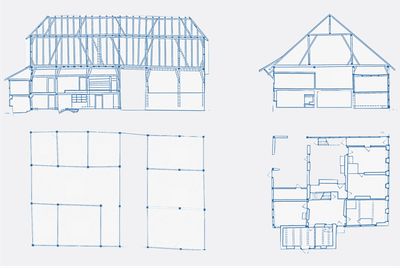

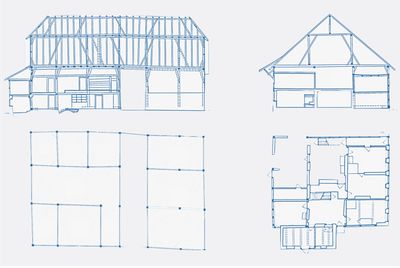

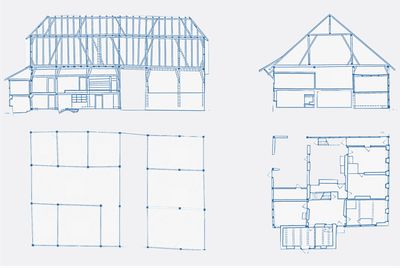

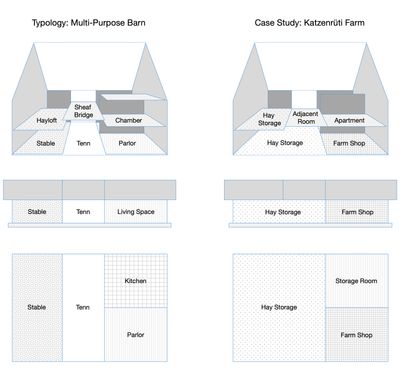

The orientation of the multi-purpose farmhouse in the canton of Zurich is determined by the sunlight, traffic axes, and the terrain. The preferred orientation is typically from east to west, with the barn on the west side. The living area, which is on the weather-protected side, is usually oriented to the south. Multi-purpose farmhouses are aligned parallel to the road and accessed from the roadside. Key elements of the architectural expression include the building’s cubic shape with a hipped roof, the building materials, and the facade design. Improved transportation conditions facilitated the transport of building materials, likely contributing to a trend toward a standardization of the architectural expression of the farmhouse. The multi-purpose farmhouse is an elongated, eave-emphasized building that combines living and utility areas under one roof. The function-specific facade design reflects the spatial organization behind it. The tall threshing floor gate is designed to accommodate the high-stacked harvest wagons.

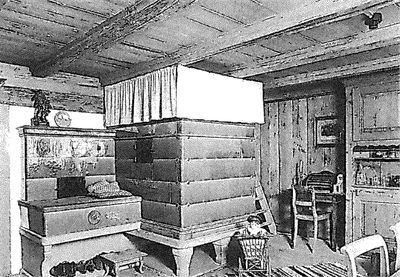

The spatial organization in a multi-purpose farmhouse comprises key areas such as the stable, hallway, parlor, kitchen, and chamber. These rooms are distributed over two stories, with the ground floor containing the parlor and kitchen. The parlor serves as the central space for daily life, work, and social interactions, while the kitchen was originally open and smoky. The kitchen also vertically connected the house, and hallways played a significant role in circulation. Throughout the centuries, there have been adaptations to the layout structures of older buildings. From the 17th century on, there was an increasing trend of subterranean storage in new constructions. In wine-producing regions, cellars served as wine or potato storage. Changing needs over the centuries led to the 20th-century practice of leveling the cellar with debris and soil, as seen in Katzenrütihof. There, the space on the ground floor serves as a hayloft instead of a stable.

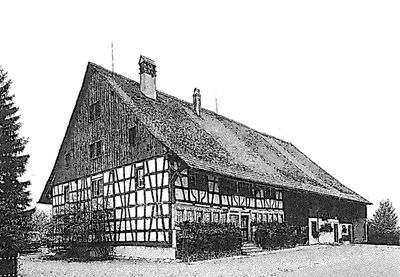

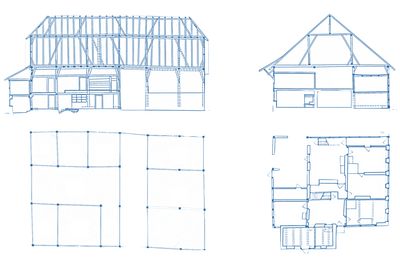

The multi-purpose farmhouse in Watt features a simple, vertically emphasized design with a timber-framed structure. It sits directly on the ground, with the basement embedded in the terrain. The dovetailed wooden joints, both functional and decorative, adorn various parts of the building. The House “Zum Spital” has seen modifications since 1538, but the main framework and roof structure remain authentic, enabling the reconstruction of the original layout. With 28 posts arranged in a grid of seven by four, it comprises a three-isled building with six cross-zones, divided into an eastern living area and a western barn, each with three cross-zones. While the House “Zum Spital” transitioned into residential and commercial use, other farms continued their agricultural practice.

From Model Farm to Storage Unit

Kleinjogg-Farm has a historical background that began with its construction in 1563. It became well-known throughout the continent when the revolutionary farmer Jakob “Kleinjogg” Guyer managed the farmstead in 1769–1785. He established a model farm, focusing on rationalizing the profession and increasing production. Cyclical thinking enabled him to increase his fertiliser availability and crop yields. Because of its history, Kleinjogg-Farm is nowadays under heritage protection.

The original building is exemplary for the farmhouse typology of Zurich. It used to be multi-functional and consisted of a tenn, a stable, and a large residence. People and animals lived separately but in harmony. They used the body heat of the animals to heat the building, in which the extended family lived together in one apartment. This state of Kleinjogg-Farm remained well into the 20th century. However, with changing ways of living and farming, there were bound to be developments.

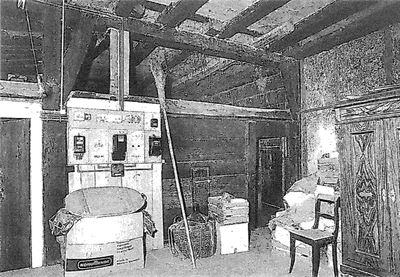

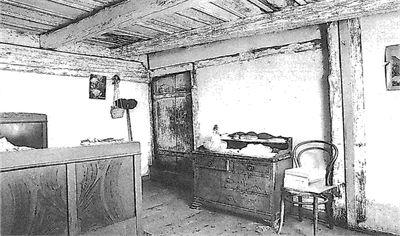

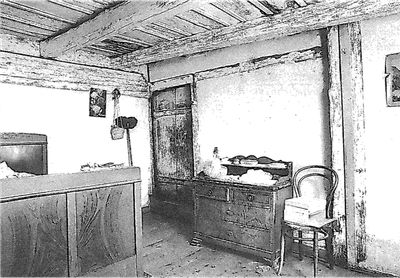

The first visible change on the farm is a consequence of the new ways of living. In 1951, the owners built a residential house with two apartments. Before that, they had already split the dwelling of the old farmhouse into two apartments. In modern times, adults want to move out of their parents’ apartment to form their own family. Privacy and independence have become essential. Nowadays Kleinjogg-Farm holds four apartments for different members of the extended family. New technologies and desires for comfort led to the construction of the cow stable in 1976. Gas emerged as the dominant form of heating, and people became upset with the stench. As a result, the animals were forced out of residential buildings. Above all, the modern ways of farming focused on technology and mass production required a modern building. Because the heritage protection and legal framework prohibited the owners from renovating the old farmhouse, they had to build a new stable. Consequently, the farmhouse is now primarily a storage unit for old machines and junk.

In summary, specialised buildings like apartments or a stable join the farm because of modern times. As a result, the once multi-functional farmhouse becomes a storage unit with some apartments.

One Origin–Four Outcomes

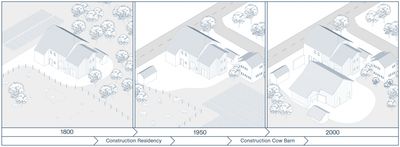

At the beginning of the 19th century, the hamlet of Katzenrüti consisted of a single farm belonging to the Guyer family. After its sale in the 1830s, three families settled close by, which initiated the development of the hamlet. Living together in a small community has several advantages for the farmers. They help each other out and share machines and livestock. New farms continually joined in the form of multipurpose buildings, which provided for all agricultural needs.

The development of Kleinjogg-Farm is not an exception but rather the rule. Said process is evident when looking at the growth and functions of Katzenrüti over the years. The development of the hamlet goes hand in hand with the expansion of the different farms. New buildings are constantly being added. Jakob Guyer rationalised agricultural practice. 150 years later we rationalised agricultural buildings.

From the second half of the 20th century on, new functions appeared in Katzenrüti. This is related to the extinction of the farms. Today, only two agricultural enterprises still exist in the hamlet: the traditional farm founded by Jakob Guyer and the Katzenrüti Hof. Both have existed since the beginning of the hamlet and were able to expand very early on. It allowed them to adapt to the industrialisation of agriculture. Farms that emerged later, were unable to adapt, and their buildings became vacant and accessible for other purposes. In our research, we noticed four types of conversions in Katzenrüti.

Some farms already changed their purpose in the 1960s. The residential part usually continued to be used but was adapted to modern living requirements. In most cases, the multi-generation dwellings were transformed into smaller rental apartments. In the economic part of the farms, some non-agricultural businesses moved in, like artist studios and car workshops. Former farmers also looked for new industries after they gave up their farms. As a result, centralised companies specialising in renting agricultural machinery and horse farms emerged.

Since the Spatial Planning Act of 1980, which is supposed to stop urban sprawl, such transformations have become more difficult. Proposals for a conversion after 1980 were rarely permitted. Consequently, vacant agricultural buildings have often become storage for machinery and cars. Almost a third of the building area is now storage space, and the maintenance of these structures is often neglected. Storage facilities are the first step towards empty and decaying buildings that have become more frequent over the last 30 years.

However, development is still taking place in Katzenrüti, driven by the inhabitants. Instead of converting vacant buildings, they plan new houses, which divides the village community. Many of the proposals are appealed, as some argue that the new projects destroy the townscape of Katzenrüti.

„The legal situation makes the construction of a new building much easier than an extension or conversion. As a result, it contributes to the urban sprawl we want to prevent.“—Family Grünenwald

Reviving Farms

Martin Gass is a farmer of Bärenbohl, who is in a peculiar but deliberate situation. Because of a tedious legal situation, he only oversees his family’s farm but does not own it. The farm’s residential house where he grew up has been vacant and decaying for the past decade. Any attempt to make it inhabitable once more is halted by Heritage Protection. Stucco on the ceiling, 220-year-old stairs, wooden flooring, and the window frames mistakenly noted as originals are some elements that Heritage Protection wants to preserve. As a result, a renovation’s cost far exceeds what any farmer could pay. This situation has stopped the potential development of the farm.

Switzerland is known to experience an increase in vacant farmhouses. Some of these have already become part of the building zone, where the obstacles to repurposing are small. However, most are still part of the agricultural zone. When thinking about development, the first step was always to check for elements we would have to preserve. Afterwards, the potential for development was decided by one key date: 1. July 1972. It determines if a building is older or younger than the Swiss zoning code. In older buildings, it was allowed to renovate dwelling spaces without changing them, so they meet contemporary standards. In newer buildings, it was generally allowed to renovate and extend the housing and possibly create a new business. In both situations, it was mandatory to preserve the local image, usually determined by shape and facade. Although these regulations are generally logical, they have prevented many farmers from redeveloping their empty buildings.

The first step to determine the need for preservation remains unchanged. But in June 2023, new regulations were enacted as part of RPG2. They allow us to transform utility buildings attached to the dwelling into houses or quiet businesses. Even a replacement building is permitted if it takes on the original shape. Prerequisites are “sufficient accessibility” and the preservation of the local image. This new legal framework might end a decade-long “lose-lose” situation around empty buildings. The barns, in particular, offer lots of potential for development and vibrant spaces. The new centralised businesses that allow farms to rent machinery instead of storing it in their barns contribute to this. Even more barns will become empty and subject to change. It is now up to creative minds to think about new ways of living inside an old farmhouse without destroying its appearance or charm.

Site Map

- Construction period until 1850

- Construction period 1850-1900

- Construction period 1900-1950

- Construction period 1950-2000

- Construction period 2000-2020

- Building zone

- Core zone

- Agricultural zone

- Recreational zone

- Reserve zone

- Forest zone

- Landscape protection zone