Zone Out:

In Between Modern Paradise

Stan Baumann

We currently find ourselves in a re-evaluation of architectural practice, which is being significantly shaped by prevailing social and ecological concerns. This transformative phase has given rise to a notable diversity of architectural approaches. As we contemplate the future roles of architects, questions naturally arise regarding the necessity to constructing. Is architectural practice fundamentally connected to the act of building?

In 1979, Andrey Tarkovsky released the movie Stalker, an adaptation of the 1972 book Roadside Picnic by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky. Thanks to Tarkovsky’s renown, the resilience lessons from Roadside Picnic when facing neglected post-industrial spaces gained global traction, evolving into a cornerstone of landscape architecture theory.

The film opens with a trio consisting of a scientist, a writer, and a guide called Stalker. Following Stalker’s guidance and engaging in specific behaviours towards the landscape, the other two are led through a post-industrial landscape known as “The Zone.” Stalker personifies the landscape, giving it a name, character, history and unique powers. The film presents a new approach to our surroundings, blending physical walks with personal psychic journeys. It introduces the theme of abandoned spaces as exit doors to society, providing shelter for outsiders and serving as a stage for self-expression.

Fast forward to the 1990s: a group of Italian architecture students, sociologists and writers confronted the rise of international-style architecture and systematic urban planning, deciding to form a collective called Stalker. They termed the negative of the urban fabric “actual territories.”

In 1993, the Stalker Collective began one of their pioneering projects: a four-day walk through the actual territories of Rome. This in situ experience encompassed activities such as sleeping, eating and rituals, and aimed to immerse participants in the heart of these spaces. The project culminated in a manifesto that defined walking as an architectural tool and articulated the essence of these spaces. By coining the term “actual territories,” the Stalker Collective sought to establish a new category of spaces within the urban fabric, akin to the Zone—a place that, unlike actual territories, exists only in Tarkovsky’s film Stalker.

In summary, while Tarkovsky’s film provided the intellectual foundation for walking and the initial exploration of abandoned spaces, the Stalker Collective developed these concepts into a comprehensive landscape theory. The main concept emerging from the Stalker manifesto is that we can only fully understand and define actual territories through in situ experience. The hidden potential of these landscapes is unveiled through the physical experience of walking through them.

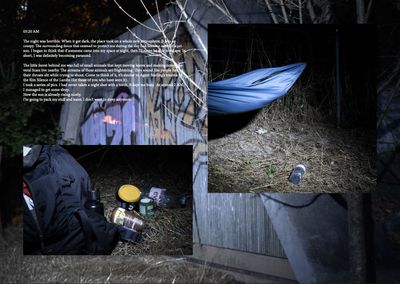

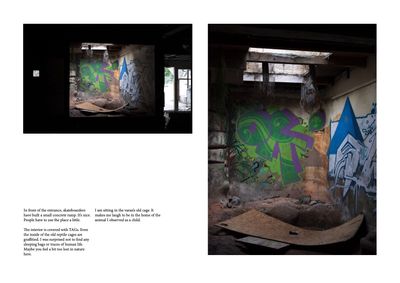

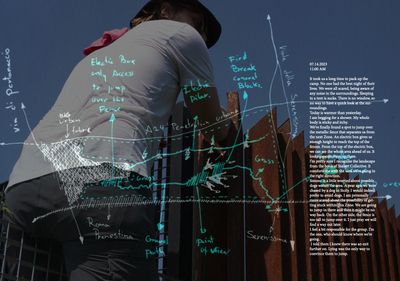

Intrigued by these theories, I decided to test them out for myself by creating a series of magazines exploring my personal views on walking as an architectural tool and the definition of actual territories. Featuring a mix of pictures and diary entries, these magazines attempt to convey my personal experiences and reflections while exploring and inhabiting actual territories in various cities and cultures.

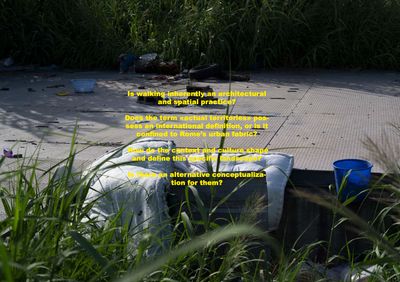

Is walking inherently an architectural and spatial practice? Does the term “actual territories” have an international definition, or is it confined to Rome’s urban fabric? How do context and culture shape and define this specific landscape? Is there an alternative conceptualisation of them?

However, it’s important to remember that these magazines are the product of personal perspectives and reflections, resulting in subjective definitions and manifestos. The true purpose of these magazines is to inspire you to explore these territories for yourself and foster your own unique ideas and experiences.