Kunstspaziergänge

Julian Daniel and Linus Bröcker

In the urban space of Zurich there are more than 1350 sculptures, fountains, and reliefs. Some are monuments, dedicated to a person; Some commemorate a historic event, most are a work of art. Some seem to be random, whilst others are famous. Yet we don’t recognise them. We pass by, not knowing their past, or why they were erected in the first place. We don’t question their existence.

Perhaps, because they are large in number, the art works become ubiquitous to a point where we do not recognise them consciously. Robert Musil states in 1935: “The most striking thing about monuments is that you don’t notice them. There is nothing in the world that is as invisible as monuments.” As technology evolves this phenomenon becomes more evident.

Art in urban space competes on two layers with the progress of technology. On the one hand, In the physical urban space: technological hardware demands more and more capacity. On the other hand, in the space of attention. Not only is evermore time spent in the digital realm, but technology determines what we see in the physical reality. As Paul Virilio puts it: “It is no longer the eye or the retina that does the work of seeing but the post-organic optical capacities of the auto-electronic machine (…).”

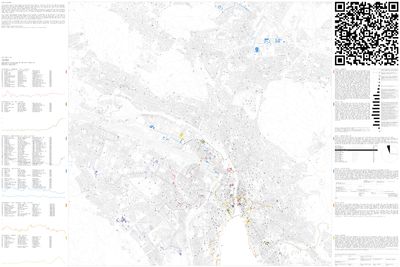

Our work, a physical map, is an attempt to give art in public space new focus. Six topics are visualised in six walks through the City of Zurich and try to raise critical questions within the context of art in public space. It could serve as a first starting point to navigate the complex relations between art, architecture, urban fabric and bureaucracy.

The map: six walks to Zurich’s public art.

Walk 01—Chronology

The development of art in architecture in Zurich began in the Middle Ages with sculptural religious and mythical figures integrated into building façades. House signs and façade decorations, such as those on the Grossmünster or the guild houses, were often highly sculptural and closely connected to the architecture. These artworks served not only as decoration but also as symbolic representations of power and faith. In the 19th century, architectural art shifted to the façades of public and institutional buildings, such as the Swiss National Museum or ETH Zurich. Stone reliefs and statues, often with national and historical themes, were integrated into the façades, giving these structures a monumental character. The strong plasticity of the works emphasized the representative function of the buildings. In the early 20th century, architectural art began to change. The plasticity of the reliefs diminished, and flatter depictions became prominent, often on residential and cooperative buildings. These works more directly reflected the everyday work and lives of the residents, such as idealized representations of workers by artists like Wilhelm Hartung and Franz Fischer. The artworks lost their depth effect but remained closely tied to the function of the buildings and conveyed a socio-political message. After World War II, architectural art became freer and modern. Sculptural works often appeared independently of the building structure. Artists like Peter Hächler and Peter Meister created abstract works and complex spatial structures that not only adorned but also defined and transformed spaces in their own right.

Walk 02—Zoo

In Zurich, exotic animals are not only to be found in the Zoo, but are scattered all over the city. Especially at the beginning of the 20th century, globalization, colonization and scientific discoveries led to a growing interest in animal sculptures and brought the diversity of nature back into the city, albeit artificial. This development fits within the broader context of the attempt to satisfy the need for recreation and contemplation for the constantly growing number of workers in the city with new parks and green spaces. The animals depicted are not limited to native species; they include numerous animals from other continents and climatic zones, reflecting the fascination with the “other” and “exotic” of that time. While some of them are linked to their context: Penguins and sea lions adorn fountains, flamingos linger in ponds. Other scenes seem rather out of context and raise the question of the initial intention and historical narrative.

Walk 03—WOMAN IN PUBLIC ART

Urban art set out with the promise to bring art out of the exclusive confines of museums and into freely accessible public spaces, making it more democratic. In the city of Zurich alone, there are over 1,350 works of public art, yet just 30 artists are responsible for roughly one-quarter of these creations. Equally striking is the gender imbalance: only 6% of the artworks—around 80 pieces—were created by 23 women. This concentration of authorship raises questions about the degree of inclusivity and diversity in public art production. Who decides what fills our urban spaces? Do institutional or market forces shape these choices? What are the social and political processes that produce art in our public spaces?

Walk 04—State of the Art

Resolution of the City Council, December 15, 2021 (translated into english from german original):

"As a result of the research project ‘Art Public Zurich’ (Kunst Öffentlichkeit Zürich), which was co-financed by the City Council (City Council Resolution [STRB] No. /2004), the permanent working group Art in Public Space (AG KiöR) was established in spring 2006 with STRB No. /2006. At the same time, a specialist office for art and architecture was created within the Office for Structural Engineering (AHB). This laid the foundation for the organization Art in Public Space (Organisation KiöR) and for a professional and contemporary approach by the city to art in public spaces. (…)Since then, the stated goals of the Organisation KiöR have included engaging with art in public spaces through art projects, as well as related public relations and outreach activities.” Has this newly established organisational commission led to more diverse and equal art in public space? Is the result more representative of our society?

Walk 05—Offset

The location of a sculpture determines its expressions. When it changes the inscribed meaning shifts. Historically sculptures were often removed from their original location and relocated. The Romans stole an obelisk from the Egyptians in 37 AD and shipped it to Rome. After Napoleon I. brought the Quadriga from Berlin to Paris, she was returned only a few years later. And after the collapse of the Soviet Union many statues of former political leaders were demolished, overwriting the commemorative significance of a place. A relocation was a symbol of a political intention. Contrary the artist Jan Morgenthaler turned the act of relocating into an artwork itself. The four most prominent monuments in Zurich were moved from their original location: e.g., the statue of Alfred Escher was relocated from main station to Hardbrücke and finds itself in a completely contrary context. The glamorous Bahnhofstrasse was suddenly replaced by concrete infrastructure realities. The artist writes, that Escher was “(…) exposed for a season to the results of his own strategic visions.”

Walk 06—Phantoms

Traditionally, sculptures and monuments are associated with permanence. However, the reality is far more dynamic: sculptures in public spaces are not static objects, but the result of social negotiation processes. Only a few of these works are actually permanent; many only remain in the city temporarily. Some are extensively discussed but never realised, and nevertheless almost part of the city’s art landscape. In his text “Zurich’s Delay”, Philipp Ursprung compares Sol LeWitt’s never realised but widely discussed artwork White Cube with Harald Naegeli’s impulsive and often illegal graffiti, an example of tension between institutionalized and spontaneous art. He states: “When I look back, there is actually only one case of art in public space in Zurich that has achieved international renown, namely the pictures of the Zurich Sprayer between 1977 and 1979.” Perhaps it is precisely these temporary and spontaneous works that are of greater interest. They can be more provocative and experimental, a challenge to society. When a work then vanishes from its established location, it leaves behind a “phantom”—a lingering trace that amplifies public attention and debate.

Photogrammetric scans of public artworks.

Sources

Bernadette Fülscher. Die Kunst im öffentlichen Raum der Stadt Zürich: 1300 Werke – Eine Bestandesaufnahme. Zurich: Chronos Verlag, 2012.

Håkan Nilsson. Placing Art in the Public Realm. Huddinge: Södertörn University, 2012.

Nicolas Whybrow. Art and the City. Dublin: I.B. Tauris, 2010.